The Museum's mission is to advance and share the experience and knowledge of what has happened in the past and what this has meant for Native peoples today; to preserve the memory of those who died or suffered; to offer comfort, support, encouragement and understanding; and to encourage its visitors to reflect upon the need for dignity of, and respect among all peoples.

You are invited to explore this Virtual Museum at your leisure and visit us frequently.

The Native American Holocaust Museum supports scholarship in the field of Native American Holocaust studies, including the publication of scholarly research.

The Museum's publication program includes scholarly works, personal accounts and testimonies of Native peoples, bibliographic works, and collections of photographic and documentary evidence.

Authors are encouraged to submit their manuscripts to NAHMUS for consideration. To maintain the identity of this site, only manuscripts by Native peoples as defined in 25 C.F.R. sec. 40.1 will be accepted for publication. At the time of manuscript submittal, tribal affiliation information must be submitted.

SCHOLARLY ARTICLES

Table of Contents

Lifelong Disparities among Older American Indians and Alaska Natives (LINK PDF)

Posted November, 2015, a Public Policy Institute research report from AARP

Page Contents:

Introduction

Kevin Gover, Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs, Statement on BIA

Mascot Articles

Civil Rights Commission Statement on Indian Mascots

Text of S.J. RES. 37: Apology to Native Peoples

President Obama Signs Native American Apology Resolution - Text of S.J. RES.4: Apology to Native Peoples

Neil Steinberg, "The Name Blame Game"

Artistic Commentary to Mr. Steinberg

Response to Mr. Steinberg

Neil Steinberg, "Atoning For America's Sins..."

Archaeology in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Understanding and Working with Students and Adults from Poverty

Recognizing an American Holocaust

Canada Agrees to Reparations for All Residential School Students (LINK)

Introduction

The articles at this site are critical to understanding the Native American Holocaust. They include: Remarks of Kevin Gover, Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior, at the Ceremony Acknowledging the 175th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, September 8, 2000, in which he states: "We must first reconcile ourselves to the fact that the works of this agency have at various times profoundly harmed the communities it was meant to serve."

Mascot Articles: I have only included the Civil Rights Commission Statement on Indian Mascots, Mon, 16 Apr 2001 but refer the reader to the Internet to all of the courageous work done by Suzanne Harjo on this subject.

Civil Rights Commission Statement on Indian Mascots, Mon, 16 Apr 2001 16:23:48 -0600, The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calls for an end to the use of Native American images and team names by non-Native schools. The Commission deeply respects the right of all Americans to freedom of statement under the First Amendment and in no way would attempt to prescribe how people can express themselves. However, the Commission believes that the use of Native American images and nicknames in schools is insensitive and should be avoided. In addition, some Native American and civil rights advocates maintain that these mascots may violate anti-discrimination laws.

Text of S.J.RES.37: Apology to Native Peoples, WEDNESDAY, MAY 19, 2004, The following is the text of S.J.RES.37, a bill to acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States, as introduced on April 6, 2004.

Text of S.J.RES.4: Apology to Native Peoples, signed by President Obama on December 19, 2009.

The Chicago Sun-Times - Neil Steinberg's April 15, 2001, op-ed piece, The name blame game and Response to Neil Steinberg op-ed piece (Not printed in full in The Chicago Sun-Times.) These articles demonstrate the spillover of the mascot issue into areas other than sports. Neil Steinberg's articles are extremely profane and derogate native peoples. They can be studied as representative of blatant, unaware, cultural, internalized and institutional racism.

Early Indian site found in downtown dig, TOM SHARPE, The New Mexican, October 22, 2004 Excavations near the Sweeney Center, in preparation for building a modern civic and convention center at the site, have unearthed human remains and pre-Columbian ruins, according to two archaeologists familiar with the area. For years, Abbott and Scheick said, significant archaeological finds in Santa Fe have been covered up by archaeologists who have falsely maintained there was no need for detailed archaeology because the artifacts found around town were the result of "fill" -- that is, earth hauled in from outlying areas.

In the early 1990s, Scheick said, archaeologists began to find evidence documenting "this sort of fantasy folklore about the pueblo under Santa Fe." "If you're going to be doing massive construction on the scale of the civic center, you really have to do full-blown archaeology, because otherwise, you're going to have bodies in the back dirt," Abbott said. "You're not going to be able to put blade to earth without running into archaeology."

Understanding and Working with Students and Adults from Poverty, Ruby K. Payne, Ph.D., aha! Process, Inc. To understand and work with students and adults from generational poverty, a framework is needed. This analytical framework is shaped around these basic ideas: individual has eight resources, which greatly influence achievement; money is only one. Poverty is the extent to which an individual is without these eight resources. The hidden rules of the middle class govern schools and work; students from generational poverty come with a completely different set of hidden rules and do not know middle class hidden rules. Language issues and the story structure of casual register cause many students from generational poverty to be unmediated, and therefore, the cognitive structures needed inside the mind to learn at the levels required by state tests have not been fully developed.

Recognizing an American Holocaust, James A. Washinawatok.

Testimony of Mr. Kevin Gover, September 8, 2000

Remarks of Kevin Gover, Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior, at the Ceremony Acknowledging the 175th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, September 8, 2000

In March of 1824, President James Monroe established the Office of Indian Affairs in the Department of War. Its mission was to conduct the nation's business with regard to Indian affairs. We have come together today to mark the first 175 years of the institution now known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

It is appropriate that we do so in the first year of a new century and a new millennium, a time when our leaders are reflecting on what lies ahead and preparing for those challenges. Before looking ahead, though, this institution must first look back and reflect on what it has wrought and, by doing so, come to know that this is no occasion for celebration; rather it is time for reflection and contemplation, a time for sorrowful truths to be spoken, a time for contrition.

We must first reconcile ourselves to the fact that the works of this agency have at various times profoundly harmed the communities it was meant to serve. From the very beginning, the Office of Indian Affairs was an instrument by which the United States enforced its ambition against the Indian nations and Indian people who stood in its path. And so, the first mission of this institution was to execute the removal of the southeastern tribal nations. By threat, deceit, and force, these great tribal nations were made to march 1,000 miles to the west, leaving thousands of their old, their young and their infirm in hasty graves along the Trail of Tears.

As the nation looked to the West for more land, this agency participated in the ethnic cleansing that befell the western tribes. War necessarily begets tragedy; the war for the West was no exception. Yet in these more enlightened times, it must be acknowledged that the deliberate spread of disease, the decimation of the mighty bison herds, the use of the poison alcohol to destroy mind and body, and the cowardly killing of women and children made for tragedy on a scale so ghastly that it cannot be dismissed as merely the inevitable consequence of the clash of competing ways of life. This agency and the good people in it failed in the mission to prevent the devastation. And so great nations of patriot warriors fell. We will never push aside the memory of unnecessary and violent death at places such as Sand Creek, the banks of the Washita River, and Wounded Knee.

Nor did the consequences of war have to include the futile and destructive efforts to annihilate Indian cultures. After the devastation of tribal economies and the deliberate creation of tribal dependence on the services provided by this agency, this agency set out to destroy all things Indian.

This agency forbade the speaking of Indian languages, prohibited the conduct of traditional religious activities, outlawed traditional government, and made Indian people ashamed of who they were. Worst of all, the Bureau of Indian Affairs committed these acts against the children entrusted to its boarding schools, brutalizing them emotionally, psychologically, physically, and spiritually. Even in this era of self -determination, when the Bureau of Indian Affairs is at long last serving as an advocate for Indian people in an atmosphere of mutual respect, the legacy of these misdeeds haunts us. The trauma of shame, fear and anger has passed from one generation to the next, and manifests itself in the rampant alcoholism, drug abuse, and domestic violence that plague Indian country. Many of our people live lives of unrelenting tragedy as Indian families suffer the ruin of lives by alcoholism, suicides made of shame and despair, and violent death at the hands of one another. So many of the maladies suffered today in Indian country result from the failures of this agency. Poverty, ignorance, and disease have been the product of this agency's work.

And so today I stand before you as the leader of an institution that in the past has committed acts so terrible that they infect, diminish, and destroy the lives of Indian people decades later, generations later. These things occurred despite the efforts of many good people with good hearts who sought to prevent them. These wrongs must be acknowledged if the healing is to begin.

I do not speak today for the United States. That is the province of the nation's elected leaders, and I would not presume to speak on their behalf. I am empowered, however, to speak on behalf of this agency, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and I am quite certain that the words that follow reflect the hearts of its 10,000 employees.

Let us begin by expressing our profound sorrow for what this agency has done in the past. Just like you, when we think of these misdeeds and their tragic consequences, our hearts break and our grief is as pure and complete as yours. We desperately wish that we could change this history, but of course we cannot. On behalf of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, I extend this formal apology to Indian people for the historical conduct of this agency.

And while the BIA employees of today did not commit these wrongs, we acknowledge that the institution we serve did. We accept this inheritance, this legacy of racism and inhumanity. And by accepting this legacy, we accept also the moral responsibility of putting things right.

We therefore begin this important work anew, and make a new commitment to the people and communities that we serve, a commitment born of the dedication we share with you to the cause of renewed hope and prosperity for Indian country. Never again will this agency stand silent when hate and violence are committed against Indians. Never again will we allow policy to proceed from the assumption that Indians possess less human genius than the other races. Never again will we be complicit in the theft of Indian property. Never again will we appoint false leaders who serve purposes other than those of the tribes. Never again will we allow unflattering and stereotypical images of Indian people to deface the halls of government or lead the American people to shallow and ignorant beliefs about Indians.

Never again will we attack your religions, your languages, your rituals, or any of your tribal ways. Never again will we seize your children, nor teach them to be ashamed of who they are. Never again.

We cannot yet ask your forgiveness, not while the burdens of this agency's history weigh so heavily on tribal communities. What we do ask is that, together, we allow the healing to begin: As you return to your homes, and as you talk with your people, please tell them that the time of dying is at its end. Tell your children that the time of shame and fear is over. Tell your young men and women to replace their anger with hope and love for their people. Together, we must wipe the tears of seven generations. Together, we must allow our broken hearts to mend. Together, we will face a challenging world with confidence and trust. Together, let us resolve that when our future leaders gather to discuss the history of this institution, it will be time to celebrate the rebirth of joy, freedom, and progress for the Indian Nations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was born in 1824 in a time of war on Indian people. May it live in the year 2000 and beyond as an instrument of their prosperity.

Mascot Articles

Civil Rights Commission Statement on Indian Mascots

Date: Mon, 16 Apr 2001 16:23:48 The following statement was released by the United States Commission on Civil Rights on April 13, 2001.

Commission Statement on the Use of Native American Images and Nicknames as Sports Symbols

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calls for an end to the use of Native American images and team names by non-Native schools. The Commission deeply respects the right of all Americans to freedom of statement under the First Amendment and in no way would attempt to prescribe how people can express themselves. However, the Commission believes that the use of Native American images and nicknames in schools is insensitive and should be avoided. In addition, some Native American and civil rights advocates maintain that these mascots may violate anti-discrimination laws.

These references, whether mascots and their performances, logos, or names, are disrespectful and offensive to American Indians and others who are offended by such stereotyping. They are particularly inappropriate and insensitive in light of the long history of forced assimilation that American Indian people have endured in this country. Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s many overtly derogatory symbols and images offensive to African-Americans have been eliminated. However, many secondary schools, post-secondary institutions, and a number of professional sports teams continue to use Native American nicknames and imagery. Since the 1970s, American Indians leaders and organizations have vigorously voiced their opposition to these mascots and team names because they mock and trivialize Native American religion and culture. It is particularly disturbing that Native American references are still to be found in educational institutions, whether elementary, secondary or post-secondary. Schools are places where diverse groups of people come together to learn not only the "Three Rs," but also how to interact respectfully with people from different cultures. The use of stereotypical images of Native Americans by educational institutions has the potential to create a racially hostile educational environment that may be intimidating to Indian students. American Indians have the lowest high school graduation rates in the nation and even lower college attendance and graduation rates. The perpetuation of harmful stereotypes may exacerbate these problems.

The stereotyping of any racial, ethnic, religious or other groups when promoted by our public educational institutions, teach all students that stereotyping of minority groups is acceptable, a dangerous lesson in a diverse society. Schools have a responsibility to educate their students; they should not use their influence to perpetuate misrepresentations of any culture or people. Children at the elementary and secondary levels usually have no choice about which school they attend. Further, the assumption that a college student may freely choose another educational institution if she feels uncomfortable around Indian-based imagery is a false one. Many factors, from educational programs to financial aid to proximity to home, limit a college student's choices. It is particularly onerous if the student must also consider whether or not the institution is maintaining a racially hostile environment for Indian students. Schools that continue the use of Indian imagery and references claim that their use stimulates interest in Native American culture and honors Native Americans. These institutions have simply failed to listen to the Native groups, religious leaders, and civil rights organizations that oppose these symbols.

These Indian-based symbols and team names are not accurate representations of Native Americans. Even those that purport to be positive are romantic stereotypes that give a distorted view of the past. These false portrayals prevent non-Native Americans from understanding the true historical and cultural experiences of American Indians. Sadly, they also encourage biases and prejudices that have a negative effect on contemporary Indian people.

These references may encourage interest in mythical "Indians" created by the dominant culture, but they block genuine understanding of contemporary Native people as fellow Americans. The Commission assumes that when Indian imagery was first adopted for sports mascots it was not to offend Native Americans. However, the use of the imagery and traditions, no matter how popular, should end when they are offensive. We applaud those who have been leading the fight to educate the public and the institutions that have voluntarily discontinued the use of insulting mascots. Dialogue and education are the roads to understanding. The use of American Indian mascots is not a trivial matter. The Commission has a firm understanding of the problems of poverty, education, housing, and health care that face many Native Americans. The fight to eliminate Indian nicknames and images in sports is only one front of the larger battle to eliminate obstacles that confront American Indians. The elimination of Native American nicknames and images as sports mascots will benefit not only Native Americans, but all Americans. The elimination of stereotypes will make room for education about real Indian people, current Native American issues, and the rich variety of American Indians in our country.

Text of S.J.RES.37: Apology to Native Peoples

WEDNESDAY, MAY 19, 2004

The following is the text of S.J.RES.37, a bill to acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States, as introduced on April 6, 2004. JOINT RESOLUTION To acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States. Whereas the ancestors of today's Native Peoples inhabited the land of the present-day United States since time immemorial and for thousands of years before the arrival of peoples of European descent; Whereas the Native Peoples have for millennia honored, protected, and stewarded this land we cherish;

Whereas the Native Peoples are spiritual peoples with a deep and abiding belief in the Creator, and for millennia their peoples have maintained a powerful spiritual connection to this land, as is evidenced by their customs and legends; Whereas the arrival of Europeans in North America opened a new chapter in the histories of the Native Peoples; Whereas, while establishment of permanent European settlements in North America did stir conflict with nearby Indian tribes, peaceful and mutually beneficial interactions also took place; Whereas the foundational English settlements in Jamestown, Virginia, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, owed their survival in large measure to the compassion and aid of the Native Peoples in their vicinities;

Whereas in the infancy of the United States, the founders of the Republic expressed their desire for a just relationship with the Indian tribes, as evidenced by the Northwest Ordinance enacted by Congress in 1787, which begins with the phrase, `The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians'; Whereas Indian tribes provided great assistance to the fledgling Republic as it strengthened and grew, including invaluable help to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their epic journey from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Pacific Coast; Whereas Native Peoples and non-Native settlers engaged in numerous armed conflicts; Whereas the United States Government violated many of the treaties ratified by Congress and other diplomatic agreements with Indian tribes; Whereas this Nation should address the broken treaties and many of the more ill-conceived Federal policies that followed, such as extermination, termination, forced removal and relocation, the outlawing of traditional religions, and the destruction of sacred places; Whereas the United States forced Indian tribes and their citizens to move away from their traditional homelands and onto federally established and controlled reservations, in accordance with such Acts as the Indian Removal Act of 1830; Whereas many Native Peoples suffered and perished--(1) during the execution of the official United States Government policy of forced removal, including the infamous Trail of Tears and Long Walk;

(2) during bloody armed confrontations and massacres, such as the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 and the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890; and

(3) on numerous Indian reservations; Whereas the United States Government condemned the traditions, beliefs, and customs of the Native Peoples and endeavored to assimilate them by such policies as the redistribution of land under the General Allotment Act of 1887 and the forcible removal of Native children from their families to faraway boarding schools where their Native practices and languages were degraded and forbidden; Whereas officials of the United States Government and private United States citizens harmed Native Peoples by the unlawful acquisition of recognized tribal land, the theft of resources from such territories, and the mismanagement of tribal trust funds; Whereas the policies of the United States Government toward Indian tribes and the breaking of covenants with Indian tribes have contributed to the severe social ills and economic troubles in many Native communities today; Whereas, despite continuing maltreatment of Native Peoples by the United States, the Native Peoples have remained committed to the protection of this great land, as evidenced by the fact that, on a per capita basis, more Native people have served in the United States Armed Forces and placed themselves in harm's way in defense of the United States in every major military conflict than any other ethnic group; Whereas Indian tribes have actively influenced the public life of the United States by continued cooperation with Congress and the Department of the Interior, through the involvement of Native individuals in official United States Government positions, and by leadership of their own sovereign Indian tribes; Whereas Indian tribes are resilient and determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their unique cultural identities; Whereas the National Museum of the American Indian was established within the Smithsonian Institution as a living memorial to the Native Peoples and their traditions; and Whereas Native Peoples are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, and that among those are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

SECTION 1. ACKNOWLEDGMENT AND APOLOGY. The United States, acting through Congress--

(1) recognizes the special legal and political relationship the Indian tribes have with the United States and the solemn covenant with the land we share;

(2) commends and honors the Native Peoples for the thousands of years that they have stewarded and protected this land;

(3) acknowledges years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of covenants by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes;

(4) apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States;

(5) expresses its regret for the ramifications of former offenses and its commitment to build on the positive relationships of the past and present to move toward a brighter future where all the people of this land live reconciled as brothers and sisters, and harmoniously steward and protect this land together;

(6) urges the President to acknowledge the offenses of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land by providing a proper foundation for reconciliation between the United States and Indian tribes; and

(7) commends the State governments that have begun reconciliation efforts with recognized Indian tribes located in their boundaries and encourages all State governments similarly to work toward reconciling relationships with Indian tribes within their boundaries. SEC. 2. DISCLAIMER. Nothing in this Joint Resolution authorizes any claim against the United States or serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States.

President Obama Signs Native American Apology Resolution

President Barack Obama signed the Native American Apology Resolution into law on Saturday, December 19, 2009. The Apology Resolution was included as Section 8113 in the 2010 Defense Appropriations Act, H.R. 3326, Public Law No. 111-118.

The Apology Resolution had originally been sponsored in the Senate by Senator Sam Brownback (R-KS) as S.J. Res. 14. A companion measure, H.J. Res. 46, was also been introduced in the House by Congressman Dan Boren (D-OK) earlier this year.Senator Brownback successfully added the Apology Resolution to the Defense Appropriations Act as an amendment on the Senate floor on October 1, 2009.

Senator Brownback said that he introduced the measure “to officially apologize for the past ill- conceived policies by the US Government toward the Native Peoples of this land and re-affirm our commitment toward healing our nation’s wounds and working toward establishing better relationships rooted in reconciliation.”

The Apology Resolution states that the United States, “apologizes on behalf of the people of the

United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect

inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.”The Apology Resolution also “urges the President to acknowledge the wrongs of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land.” The Apology Resolution comes with a disclaimer that nothing in the Resolution authorizes or

supports any legal claims against the United States and that the Resolution does not settle any claims against the United States.The Apology Resolution does not include the lengthy Preamble that was part of S.J Res. 14 introduced earlier this year by Senator Brownback. The Preamble recites the history of U.S. – tribal relations including the assistance provided to the settlers by Native Americans, the killing of Indian women and children, the Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, the Sand Creek Massacre, and Wounded Knee, the theft of tribal lands and resources, the breaking of treaties, and the removal of Indian children to boarding schools.

Text of S.J. RES.4: Apology to Native Peoples>

[Congressional Bills 110th Congress]

[From the U.S. Government Printing Office]

[S.J. Res. 4 Introduced in Senate (IS)]110th CONGRESS

1st Session

S. J. RES. 4To acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-

conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian

tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the

United States.

_______________________________________________________________________

IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES

March 1, 2007

Mr. Brownback, (for himself, Mr. Inouye, Ms. Cantwell, Mr. Dodd, Ms. Landrieu, and Mr. Crapo) introduced the following joint resolution; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs

_______________________________________________________________________

JOINT RESOLUTION

To acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-

conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian

tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the

United States.Whereas the ancestors of today's Native Peoples inhabited the land of the

present-day United States since time immemorial and for thousands of

years before the arrival of peoples of European descent;

Whereas the Native Peoples have for millennia honored, protected, and stewarded

this land we cherish;

Whereas the Native Peoples are spiritual peoples with a deep and abiding belief

in the Creator, and for millennia their peoples have maintained a

powerful spiritual connection to this land, as is evidenced by their

customs and legends;

Whereas the arrival of Europeans in North America opened a new chapter in the

histories of the Native Peoples;

Whereas, while establishment of permanent European settlements in North America

did stir conflict with nearby Indian tribes, peaceful and mutually

beneficial interactions also took place;

Whereas the foundational English settlements in Jamestown, Virginia, and

Plymouth, Massachusetts, owed their survival in large measure to the

compassion and aid of the Native Peoples in their vicinities;

Whereas in the infancy of the United States, the founders of the Republic

expressed their desire for a just relationship with the Indian tribes,

as evidenced by the Northwest Ordinance enacted by Congress in 1787,

which begins with the phrase, ``The utmost good faith shall always be

observed toward the Indians'';

Whereas Indian tribes provided great assistance to the fledgling Republic as it

strengthened and grew, including invaluable help to Meriwether Lewis and

William Clark on their epic journey from St. Louis, Missouri, to the

Pacific Coast;

Whereas Native Peoples and non-Native settlers engaged in numerous armed

conflicts;

Whereas the United States Government violated many of the treaties ratified by

Congress and other diplomatic agreements with Indian tribes;

Whereas this Nation should address the broken treaties and many of the more ill-

conceived Federal policies that followed, such as extermination,

termination, forced removal and relocation, the outlawing of traditional

religions, and the destruction of sacred places;

Whereas the United States forced Indian tribes and their citizens to move away

from their traditional homelands and onto federally established and

controlled reservations, in accordance with such Acts as the Indian

Removal Act of 1830;

Whereas many Native Peoples suffered and perished--(1) during the execution of the official United States Government

policy of forced removal, including the infamous Trail of Tears and Long

Walk;(2) during bloody armed confrontations and massacres, such as the Sand

Creek Massacre in 1864 and the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890; and(3) on numerous Indian reservations;

Whereas the United States Government condemned the traditions, beliefs, and

customs of the Native Peoples and endeavored to assimilate them by such

policies as the redistribution of land under the General Allotment Act

of 1887 and the forcible removal of Native children from their families

to faraway boarding schools where their Native practices and languages

were degraded and forbidden;

Whereas officials of the United States Government and private United States

citizens harmed Native Peoples by the unlawful acquisition of recognized

tribal land and the theft of tribal resources and assets from recognized

tribal land;

Whereas the policies of the United States Government toward Indian tribes and

the breaking of covenants with Indian tribes have contributed to the

severe social ills and economic troubles in many Native communities

today;

Whereas, despite the wrongs committed against Native Peoples by the United

States, the Native Peoples have remained committed to the protection of

this great land, as evidenced by the fact that, on a per capita basis,

more Native people have served in the United States Armed Forces and

placed themselves in harm's way in defense of the United States in every

major military conflict than any other ethnic group;

Whereas Indian tribes have actively influenced the public life of the United

States by continued cooperation with Congress and the Department of the

Interior, through the involvement of Native individuals in official

United States Government positions, and by leadership of their own

sovereign Indian tribes;

Whereas Indian tribes are resilient and determined to preserve, develop, and

transmit to future generations their unique cultural identities;

Whereas the National Museum of the American Indian was established within the

Smithsonian Institution as a living memorial to the Native Peoples and

their traditions; and

Whereas Native Peoples are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable

rights, and that among those are life, liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United

States of America in Congress assembled,SECTION 1. ACKNOWLEDGMENT AND APOLOGY.

The United States, acting through Congress--

(1) recognizes the special legal and political relationship

the Indian tribes have with the United States and the solemn

covenant with the land we share;

(2) commends and honors the Native Peoples for the

thousands of years that they have stewarded and protected this

land;

(3) recognizes that there have been years of official

depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of

covenants by the United States Government regarding Indian

tribes;

(4) apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States

to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence,

maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by

citizens of the United States;

(5) expresses its regret for the ramifications of former

wrongs and its commitment to build on the positive

relationships of the past and present to move toward a brighter

future where all the people of this land live reconciled as

brothers and sisters, and harmoniously steward and protect this

land together;

(6) urges the President to acknowledge the wrongs of the

United States against Indian tribes in the history of the

United States in order to bring healing to this land by

providing a proper foundation for reconciliation between the

United States and Indian tribes; and

(7) commends the State governments that have begun

reconciliation efforts with recognized Indian tribes located in

their boundaries and encourages all State governments similarly

to work toward reconciling relationships with Indian tribes

within their boundaries.SEC. 2. DISCLAIMER.

Nothing in this Joint Resolution--

(1) authorizes or supports any claim against the United

States; or

(2) serves as a settlement of any claim against the United

States.

The Chicago Sun-Times - Neil Steinberg's April 15, 2001, op-ed piece, The name blame game.

"The Front Page" was on cable the other day. Even though it was an inferior version, with Cary Grant and a female Hildy Johnson, I savored Ben Hecht and Charlie MacArthur's 1920s masterpiece.

The fact that it shows journalists in a dim light--as a bunch of card-playing, booze-swilling, cynical bastards chuckling to themselves as an innocent man heads toward the gallows--did not bother me one bit.

First, we are, or at least were, Second, it's funny. Third, it's a play. It's fiction. It doesn't have to buck me up, personally. I can enjoy it anyway. That's called being an adult. (I like "The Merchant of Venice" too, even though Shylock is not exactly a JUF poster boy.)

This view, sadly, is not shared by everyone. We are afflicted by an endless series of dreary debates by every fringe group that feels, by merit of their ethnicity, that they somehow have a right to try to seize the reins of the creative world and drive it off into their own self-congratulatory direction.

Just this week, a group of Italian Americans--not a nationality generally known for touchiness--sued "The Sopranos" TV show, claiming it damages their reputation (how fragile must your self-image be if it is threatened by a TV show?) And every day, it seems, a knot of Native Americans somewhere, or just a bunch of education-addled kids, takes exception with Chief Illiniwek, the bland mascot of University of Illinois sporting events.

It's a game anyone can play. Friday a federal civil rights panel called for an end to Indian team names and mascots at non-Indian schools, colleges and universities.

It is, of course, a free country, so far, despite their efforts, and people can complain about and protest over whatever they like. But other opinions may also be aired, and the time has come to note that being offended has become overdone. We who are not touchy zealots must not sit by while our cultural pleasures are hacked away.

The problem with judging entertainment solely on its ability to irk someone somewhere is that there is always a someone, somewhere offended by almost everything. Charlie Chaplin slipping on a banana peel might be laughed at by 999 people. But that 1000th guy, poor fellow, who slipped on a banana peel himself and broke his neck, may not find it funny. In olden times, he might have kept it to himself. But in our raging culture of complaint, no displeasure goes unvoiced, and we as a society have to decide how much we're willing to let the disgruntled few decide what is enjoyed by the oblivious many.

Not much, I'd say, because once you give into one, it's a steady slide toward blandness. Let's assume the Italian Americans suing "The Sopranos," through some inconceivable fluke, succeed in their quixotic quest. ("Dear Mr. Steinberg. I am a Spanish American, and deeply resent your dismissive reference to our national hero, El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha") Why shouldn't fat people, themselves well-organized into feel-good societies, restrain themselves in going after "The Drew Carey Show" for the maligned Mimi, or Turks picket Blockbuster video stores renting "Midnight Express"?

The result would be entertainment scrubbed clean of qualities: generic people standing around, saying nothing, doing nothing.

Those complaining would like us to focus on the merits of the art they say offends them, specifically. But we have the right to step back and ask whether we want to hand the remote control, or the keys to the theater, or the mascot makeup box, to a bunch of whiners and fusspots. I myself can't conceive of a production so foul that I would want it banned--OK maybe "The Little Mermaid"--and have no respect for those whose sole complaint is that the characters sharing their ethnicity don't match the lofty, pristine view they have of themselves.

Besides, yielding wouldn't help anyway. What if the University of Illinois caves in, as seems to be the fashion, replacing the chief with a Smiley Face or a bulldog or a feather or whatever? Do any of you imagine that the Indian activists stirring this pot will find satisfaction, and go on to productive pursuits, and stop bothering people? Doubtful. Just as the curing of polio did not end the March of Dimes, but merely inspired it to leap from one infirmity to another (birth defects carefully chosen, no doubt, so as not to be solved anytime soon), so we can expect Native-American activists, having finally dispatched the chief, will to turn their attentions to other Indian icons in the culture.

Not that we need them for this. The activist way of thinking is so depressingly familiar that we the non-offended can easily apply it to any icon, no matter how benign. Once the chief goes, here are what I imagine will be the next symbols of hatred to fall under tedious attack:

[THE PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE ARTICLE REFERRED TO BELOW WERE NOT ON WEB.]

Land O Lakes maiden: Kneeling, subservient, butter-offering "squaw" is patently offensive to the historically aware, and denies the heritage of active Native-American womanhood. When the well-known schoolboy prank is factored in (cut out the maiden's knees and slide them to cover the butter box in her hands) this obvious symbol of sexist hate can't be expected to last long into the 21st century. Expect feminists to pile in as pressure builds. Possible replacements: milk bucket, butterfly, Lakey the Llama.

Toy Indian figures: Stereotype of "savage" Indians in fighting poses is one of the most egregious throwbacks to racist past. Toy stores, having already buckled under to anti-gun hysterics (mostly non-parents and those too unobservant to notice that boys turn any object longer than it is wide into a toy gun) will probably be quick to yank these hateful homunculi from the shelves. Possible replacements: generic Old West "bad guy" figurines; Indians engaged in peaceful activities such as grinding maize.

Indiana: The butt of constant David Letterman jokes, famed for mediocrities such as Dan Quayle--what is Indiana other than an excuse to slander the proud Native-American heritage by affixing the "Indian" slur/name to a bland state where not too many Indians lived in the first place? Possible replacements: Just-ana, East Illinois.

Buffalo nickel: Only white America could be perverse enough to put an authentic portrait of a native American on one side of a coin, a buffalo on the other, then name it for the animal. Possible replacements: While the nickels, as historic coinage, cannot be eliminated, they can be renamed--as the Native American Elder Weeping that White People Ever Set Foot Here nickel.

The central mistake that activists make is the belief that the vacuum created by eliminating flawed depictions would be filled with genuine ones. Should Chief Illiniwek go, fans wouldn't rush home from football games and watch "Dances With Wolves" as compensation. They'll just forget. The last irony is, should all these symbols be wiped away, the activists would take one look at the new landscape, barren of a single feather or dab of warpaint, no matter how fake, and immediately start lobbying to bring them all back. Better to be remembered in caricature than forgotten altogether.

Reprinted under the Fair Use doctrine of international copyright law.

http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.html

(Document not obtainable on web due to archiving time limits of publisher.)

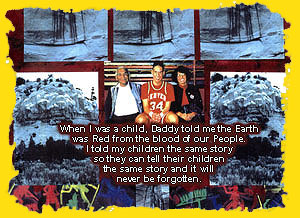

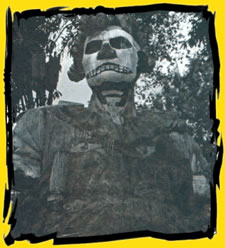

THE FOLLOWING ART OBJECTS ARE AN ARTISTIC COMMENTARY BY YAGNIZA TO MR. STEINBERG'S ARTICLE. THEY ARE NOT A PART OF HIS ARTICLE. THEIR TITLES IN ORDER BELOW ARE: SOCIAL COMMENTARY: THE INDIAN MAIDEN FANTASY, THE EARTH IS RED, TECUMSEH SHAMED (TECUMSEH IS A FAMOUS SHAWNEE LEADER WHO FOUGHT AT THE BATTLE OF TIPPECANOE IN INDIANA - HE IS SO FAMOUS THE UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY HAS A BUST OF HIM IN WHAT IS REFERRED TO AS T-COURT) AND THE BUFFALO WEPT. COPYRIGHT, YAGNIZA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. IMAGE IN THE INDIAN MAIDEN FANTASY USED SOLELY AS ARTISTIC COMMENTARY IN RESPONSE TO THE FOREGOING ARTICLE.

Response to Neil Steinberg op-ed piece (Not printed in full in The Chicago Sun-Times.)

To the editorial staff of the Chicago Sun Times,

The United States is founded on the depopulation, the dispossession, and the deconstruction of American Indian societies who are now forced to live in and through the institutions erected by the oppressing regimes.

It is of great concern that you would print the racist and hateful messages included in Neil Steinberg's April 15, 2001, op-ed piece The name blame game. The opinion piece included two incredibly disrespectful remarks: "the Native American Elder Weeping that White People Ever Set Foot Here nickel", and "Better to be remembered in caricature than forgotten altogether." Mr. Steinberg also erroneously stated that "what is Indiana other than an excuse to slander the proud Native-American heritage affixing the "Indian" slur/name to a bland state where not too many Indians lived in the first place." Indiana was home to the Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, Ho Chunk, Huron, Peton, and Miami Nations. Mr. Steinberg aggressively and ignorantly disparages our ancestors' deaths by minimizing their wholesale slaughter. Mr. Steinberg attempts to create an argument where the tens of thousands of Indiana regional Native deaths at the hands of colonists is acceptable. Are we living in Germany during World War II, or is this still twenty-first century America?

The 3,440,700 American Indian peoples of the 446 federally recognized Nations disagree with Mr. Steinberg.

According to the current anthropological debate, approximately seven million people indigenous to the borders of the USA and Canada died in the formation of these two countries. There were approximately 250,000 American Indians alive in the year 1900. Native Americans would like to end the disrespect of our ancestors' struggles for survival. Caricaturing our religious beliefs and culture through mascot and logo use must end if we are to be respected as equals in the playing field of American democracy.

Today the remaining indigenous Nations are reestablishing themselves through education, economic development, and the exploration of what it means to be sovereign Nations. One fundamental campaign is taking back our identity from the hands of an oppressive government and society. The constant objectification and dehumanization American Indians suffer in the hands of the white majority is symptomatic of the white majority's desire to remain in denial about its involvement in genocidal practices. The lack of American Indian history in public school curricula is appalling. The gross ignorance the American majority show in their responses to the American Indian mascot issue is a direct reflection of our educational welfare as a country. The current American history is not including all of the influences that helped shape the democracy we have today. A greater national awareness and a Chicago Sun Times awareness of how great a price Indigenous Nations paid in the formation of the Americas would prevent Mr. Steinberg's insensitive and racist remarks from being published in your paper.

Sincerely, Aaron Bird Bear

The Chicago Sun-Times, Neil Steinberg's April 22, 2001, op-ed piece, Atoning for America's sins shouldn't be chief concern.

One problem with being a zealot is that it blinds you to how you are perceived by people who are not zealots.

The guy prowling up and down South Wacker, for instance, wearing a homemade cardboard sandwich sign denouncing Hart, Schaffner & Marx clothiers. That guy must believe, as he slips into his sign each morning, that he is Truth's Own Proud Warrior, donning his armor.

But he doesn't seem that way to me. It's all I can do not to shout at him, "The company isn't even called that anymore, you pinhead!"

But why cause trouble?

I get enough trouble as it is. My column about the tiresome battle against Chief Illiniwek drew the inevitable outrage and demands for my "immediate dismissal." (Oh, Sylvan dream! And just as the warm weather hits. "Honey, would you grab me a cold beer and see if the unemployment check is here yet?")

Anyway, among the letters and calls and e-mails was a message from Aaron Bird Bear of Madison, Wis. It begins:

"The United States is founded on the depopulation, the dispossession, and the deconstruction of American Indian societies who are now forced to live in and through the institutions erected by the oppressing regimes."

I agree completely with that statement. It is utterly true. Though I would quibble over the last two words. What Mr. Bird Bear calls "oppressing regimes" I would refer to as "our beloved country."

That's the heart of the problem. Their ceiling is my floor. I certainly don't deny them their perspective. Native Americans are within their right to view this country as forever tainted by the crimes against Indians. It doesn't change things, but if it helps them cope, why not?

One doesn't have to be very imaginative to understand the Indian view: This is their house, stolen, now occupied by their smirking oppressors who, to add insult to literal injury, trot out these sports mascots, oafish parodies of the proud people who once roamed these lands before being murdered and traduced.

Mr. Bird Bear finds a direct connection between the two.

"The constant objectification and dehumanization American Indians suffer in the hands of the white majority is symptomatic of the white majority's desire to remain in denial about its involvement in genocidal practices," he writes.

Here is where he begins to lose me. Just as Jesse Jackson's desire to load the guilt of slavery onto 2001 America's shoulders, the idea of white people in America today having "an involvement in genocidal practices" is problematic.

My family, for instance, was busy scratching out a living in dirt villages in Poland while the Indians were getting the boot. Does the fact that my forebears just managed to flee to Poland ahead of their own grinding steamroller of history mean that suddenly we killed the Indians and therefore can't like Chief Wahoo? I don't get it.

History is a hard place. People win and people lose. The next fact that should be taught in school after the horrendous cruelties against the Indians is that our nation would have hardly been able to form had they been treated otherwise. Had this big Indian nation been allowed to exist in the heartland of America, that would have been swell for them, but our nation wouldn't have grown into the power it became.

We'd be more like Australia, a few big cities along the coasts and a big empty space in the middle. Good for Indians there, bad for the country around it and worse for the world. I don't like to play "what if' with history--it's a meaningless exercise-but you can bet if the Spanish/English nightmare hadn't descended on the Indians 500 years ago, then the Nazi/Japanese nightmare would have 50 years ago or the Chinese/Chinese nightmare next year. History is not often kind to spiritual native peoples whose technology is based on buckskin.

I wish I could explore other aspects of Mr. Bear Bird's letter, such as his faulting me for a variety of "incredibly disrespectful remarks," such as my suggestion that Indian activists would have the Buffalo nickel be renamed "the Native American Elder Weeping That White People Ever Set Foot Here" nickel.

Flippant, perhaps. But I'm not really sure what I'm being accused of not respecting. The idea that America should always be viewed as a charnel house because of its crimes against Indians? Guilty. The idea that those crimes give Native Americans now the moral authority to tell everybody else what to do? Again guilty. I don't respect that. I don't respect a lot of grim-faced crybabies who view this country as a series of "oppressive regimes" they are forced to endure.

And I don't agree that the sports mascots are offensive. Oh, I know the activists are offended, but then that's their bread and butter.

Put it this way. A few months ago I passed through the airport in Copenhagen, Denmark. The shops were filled with those comical, squat Viking figures, with bushy beards, huge noses and horned helmets.

Those Viking dolls are as crude a parody as anything dancing at a football game. The Danes love 'em, because they don't have any Viking Activist Groups talking about respect. Lucky Danes.

Reprinted under the Fair Use doctrine of international copyright law.

http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.html

(Document not obtainable on web due to archiving time limits of publisher.)

Archaeology in Santa Fe, New Mexico

TOM SHARPE | The New Mexican

October 22, 2004

Excavations near the Sweeney Center, in preparation for building a modern civic and convention center at the site, have unearthed human remains and pre-Columbian ruins, according to two archaeologists familiar with the area.

Alysia Abbott and Cherie Scheick, who tried to bid on the city contract for the archaeological investigation, say test pits by the state Office of Archaeological Studies revealed American Indian graves, trash pits and structures.

"I don't know for sure what it is," Abbott said. "But I do know that they hit human bone and, in this archaeological context, there are probably burials everywhere."

Scheick said the initial findings lends credence to the theory that Santa Fe is built atop the ruins of a Pueblo Indian settlement, and downtown is "one huge archaeological site."

So far, city and state officials won't confirm the reports of human remains and other significant finds that might slow plans to build a new civic center.

Stephen Lentz, supervisory archaeologist for the recent state dig in the parking lot between the Sweeney Center and City Hall, acknowledged that pottery, animal bones and "lithic," or stone artifacts, were found. But asked about human remains, he said, "I'm not at liberty to say."

Frank Romero, the city's project manager for the convention-center project, said he had been told animal bones were found in the test pits, but knows of no human remains or other significant archaeological finds. City Manager Mike Lujan said the state agency plans to present a report on its findings by Nov. 18.

But Steve Post, a state archaeologist on the city Archaeological Review Committee, told the committee Thursday that the findings are "fulfilling all expectations" by revealing multiple pit houses, ceramics and other proof of habitation 700 to 800 years ago. "The archaeologists are concerned that they're being pressured to make predictions about what's under the Sweeney Center," he said.

Post said it has been suggested an auger be used to look for artifacts from a crawl space under the convention center.

Abbott, who worked as a preservation planner for Santa Fe city government until she started her own archaeological-consulting business, Abboteck, last year, and Scheick, who has done archaeology work for 20 years through her business, Southwest Archaeological Consultants, are protesting how the city chose the state agency to conduct archaeological testing on city property.

They say they tried to bid on the second phase of the work, called data collection, even though they found out about the city's request for proposals, known as an RFP, only days before the deadline. Even though their bid was rejected because they were too late, they say, their protests caused city officials to withdraw the RFP and to reconsider how the contract will be let.

"What we're trying to do is to get them to realize that they have a flawed process," Scheick said. "Whether deliberately or unwittingly, they manipulated the RFP to benefit a state agency, and as a small business practicing here for years, that just doesn't seem right."

For years, Abbott and Scheick said, significant archaeological finds in Santa Fe have been covered up by archaeologists who have falsely maintained there was no need for detailed archaeology because the artifacts found around town were the result of "fill" -- that is, earth hauled in from outlying areas.

In the early 1990s, Scheick said, archaeologists began to find evidence documenting "this sort of fantasy folklore about the pueblo under Santa Fe." She said artifacts have been found along McKenzie Street, near the Lensic Performing Arts Center, First Presbyterian Church and elsewhere on the northwest side of downtown. Three or four years ago, she said, she excavated four or five burials and a huge trash pit near the Awakening Gallery at Johnson and Guadalupe streets.

Federal law calls for licensed archaeologists to move pre-Columbian human remains to an area outside the project area with the assistance of "tribes affiliated with the burial sites," she said. The Santa Fe artifacts appear to be from early Pueblo cultures dating back to 1200 A.D., she said.

Scheick said her firm recently excavated a "pit structure" 3 feet beneath the surface near the U.S. Courthouse, just north of City Hall.

"So we had a real vested interest in this site, I've got to admit," she said. "We felt that if anyone is going to tackle this project, we were as good a candidate as anyone, because we had done more in this particular period of archaeology in town than anyone else."

Abbott and Scheick say the area probably also holds many artifacts from Spanish colonial and early U.S. territorial times, but the pre-Columbian relics are likely to be so significant as to warrant preservation and incorporation into the design of the new civic center.

"If you're going to be doing massive construction on the scale of the civic center, you really have to do full-blown archaeology, because otherwise, you're going to have bodies in the back dirt," Abbott said. "You're not going to be able to put blade to earth without running into archaeology."

Understanding and Working with Students and Adults from Poverty

By: Ruby K. Payne, Ph.D., Founder and president of aha! Process, Inc., Extracted from BC Alternative Education Association Newsletter, Volume 15, Number 1, Spring 2004

Although this article was originally written for teachers, the information presented may be of help to those who are working with persons making the transition from welfare to work.

To understand and work with students and adults from generational poverty, a framework is needed. This analytical framework is shaped around these basic ideas:

·Each individual has eight resources, which greatly influence achievement; money is only one.

·Poverty is the extent to which an individual is without these eight resources.

·The hidden rules of the middle class govern schools and work; students from generational poverty come with a completely different set of hidden rules and do not know middle class hidden rules.

·Language issues and the story structure of casual register cause many students from generational poverty to be unmediated, and therefore, the cognitive structures needed inside the mind to learn at the levels required by state tests have not been fully developed.

·Teaching is what happens outside the head; learning is what happens inside the head. For these students to learn, direct teaching must occur to build these cognitive structures.

·Relationships are the key motivators for learning for students from generational poverty.

Key points

Here are some key points that need to be addressed before discussing the framework:

Poverty is relative. If everyone around you has similar circumstances, the notion of poverty and wealth is vague. Poverty or wealth only exists in relationship to the known quantities or expectation.

Poverty occurs among people of all ethnic backgrounds and in all countries. The notion of a middle class as a large segment of society is a phenomenon of this century. The percentage of the population that is poor is subject to definition and circumstance.

Economic class is a continuous line, not a clear-cut distinction. Individuals move and are stationed all along the continuum of income.

Generational poverty and situational poverty are different. Generational poverty is defined as being in poverty for two generations or longer. Situational poverty exists for a shorter time and is caused by circumstances like death, illness, or divorce. This frame-work is based on patterns. All patterns have exceptions.

An individual brings with them the hidden rules of the class in which they were raised. Even though the income of the individual may rise significantly, many patterns of thought, social interaction, cognitive strategies, and so on remain with the individual.

School and businesses operate from middle-class norms and use the hidden rules of the middle class. These norms and hidden rules are never directly taught in schools or in businesses.

We must understand our students’ hidden rules and teach them the hidden middle-class rules that will make them successful at school and work. We can neither excuse them nor scold them for not knowing; we must teach them and provide support, insistence, and expectations.

To move from poverty to middle class or from middle class to wealth, an individual must give up relationships for achievement.

Resources

Poverty is defined as the "extent to which an individual does without resources." These are the resources that influence achievement:

Financial: the money to purchase goods and services.

Emotional: the ability to choose and control emotional responses, particularly to negative situations, without engaging in self-destructive behaviour. This is an internal resource and shows itself through stamina, perseverance, and choices.

Mental: the necessary intellectual ability and acquired skills, such as reading, writing, and computing, to deal with everyday life.

Spiritual: a belief in divine purpose and guidance.

Physical: health and mobility. Support systems: friends, family, backup resources and knowledge bases one can rely on in times of need. These are external resources.

Role models: frequent access to adults who are appropriate and nurturing to the child, and who do not engage in self-destructive behaviour.

Knowledge of hidden rules: knowing the unspoken cues and habits of a group.

Language and Story Structure

To understand students and adults who come from a background of generational poverty, it’s helpful to be acquainted with the five registers of language. These are frozen, formal, consultative, casual, and intimate.

Formal register is standard business and educational language. Formal register is characterized by complete sentences and specific word choice.

Casual register is characterized by a 400 to 500 word vocabulary, broken sentences, and many non-verbal assists. Maria Montano-Harmon, a California researcher, has found that many low-income students know only casual register. Many discipline referrals occur because the student has spoken in casual register.

When individuals have no access to the structure and specificity of formal register, their achievement lags. This is complicated by the story structure used in casual register.

In formal register, the story structure focuses on plot, has a beginning and end, and weaves sequence, cause and effect, characters, and consequences into the plot.

In casual register, the focus of the story is characterization. Typically, the story starts at the end (Joey busted his nose), proceeds with short vignettes interspersed with participatory comments from the audience. (He hit him hard. BAMBAM. You shouda’ seen the blood on him), and finishes with a comment about the character. (To see this in action, watch a TV talk show where many of the participants use this structure.) The story elements that are included are those with emotional significance for the teller. This is an episodic, random approach with many omissions. It does not include sequence, cause and effect, or consequence.

Cognitive Issues

The cognitive research indicates that early memory is linked to the predominant story structure that an individual knows. Furthermore, stories are retained in the mind longer than many other memory patterns for adults. Consequently, if a person has not had access to a story structure with cause and effect, consequence, and sequence, and lives in an environment where routine and structure are not available, she or he cannot plan.

According to Reuven Feuerstein, and Israeli educator:

·Individuals who cannot plan, cannot predict.

·If they cannot predict, they cannot identify cause and effect.

·If they cannot identify cause and effect, they cannot identify consequence.

·If they cannot identify consequence, they cannot control impulsivity.

·If they cannot control impulsivity, they have an inclination to criminal behaviour.

Mediation

Feuerstein refers to these students as "unmediated." Simply explained mediation happens when an adult makes a deliberate intervention and does three things:

·points out the stimulus (what needs to be paid attention to)

·gives the stimulus meaning

·provides a strategy to deal with the stimulus.

For example: Don’t cross the street without looking (stimulus). You could be killed (meaning). Look twice both ways before crossing (strategy).

Mediation builds cognitive strategies for the mind. The strategies are analogous to the infrastructure of a house, that is, the plumbing, electrical and heating systems. When cognitive strategies are only partially in place, the mind can only partially accept the teaching. According to Feuerstein, unmediated students may miss as much as 50 percent of text on a page.

Why are so many students unmediated? Poverty forces one’s time to be spent on survival. Many students from poverty live in single parent families. When there is only one parent, she or he does not have time and energy to both mediate the children and work to put food on the table. And if the parent is non-mediated, her or his ability to mediate the children will be significantly lessened.

To help students learn when they are only partially mediated, four structures must be built as part of direct teaching:

·the structure of the discipline,

·cognitive strategies,

·conceptual frameworks, and

·models for sorting out what is important from what is unimportant in text.

Hidden Class Rules

(A) Generational Poverty

(B) Middle Class

(C) Wealth

(A) The driving forces for decision-making are survival, relationships, and entertainment.

(B) The driving forces for decision-making are work and achievement.

(C) The driving forces for decision-making are social, financial, and political connections.

(A) People are possessions. It is worse to steal someone’s girlfriend than a thing. A relationship is valued over achievement. That’s why you must defend your child no matter what she or he has done. Too much education is feared because the individual might leave.

(B) Things are possessions. If material security is threatened, often the relationship is broken.

(C) Legacies, one-of-a-kind objects, and pedigrees are possessions.

(A) The "world" is defined in local terms.

(B) The "world" is defined in national terms.

(C) The "world" is defined in international terms.

(A) Physical fighting is how conflict is resolved. If you only know casual register, you don’t have the words to negotiate a resolution. Respect is accorded to those who can physically defend themselves.

(B) Fighting is done verbally. Physical fighting is reviewed with distaste.

(C) Fighting is done through social inclusion/exclusion and through lawyers.

(A) Food is valued for its quantity.

(B) Food is valued for its quality.

(C) Food is valued for its presentation.

Other Rules

· You laugh when you are disciplined; it is a way to save face.

· The noise level is higher, nonverbal information is more important than verbal. Emotions are openly displayed, and the value of personality to the group is your ability to entertain.

· Destiny and fate govern. The notion of having choices is foreign. Discipline is about penance and forgiveness, not change.

· Tools are often not available. Therefore, the concepts of repair and fixing may not be present.

· Formal register is always used in an interview and is often an expected part of social interaction.

· Work is a daily part of life.

· Discipline is about changing behaviour. To stay in the middle class, one must be self-governing and self-supporting.

· A reprimand is taken seriously (at least the pretense is there), without smiling and with some deference to authority.

· Choice is a key concept in the lifestyle. The future is very important. Formal education is seen as crucial for future success.

· The artistic and aesthetic are key to the lifestyle and include clothing, art, interior design, seasonal decorating, food, music, social activities, etc.

· For reasons of security and safety, virtually all contacts dependent on connection and introductions.

· Education is for the purpose of social and political connections, as well as to enhance the artistic and aesthetic.

· One of the key differences between the well-to-do and the wealthy is that the wealthy almost always are patrons to the arts and often have an individual artist(s) to whom they are patrons as well.

· The hidden rules of the middle class must be taught so students can choose to follow them if they wish.

Hidden Rules

One key resource for success in school and at work is an understanding of the hidden rules. Hidden rules are the unspoken cueing system that individuals use to indicate membership in a group. One of the most important middle-class rules is that work and achievement tend to be the driving forces in decision-making. In generational poverty, the driving forces are survival, entertainment, and relationships. This is why a student may have a $30 Halloween costume but an unpaid book bill.

Hidden rules shape what happens at school. For example, if the rule a student brings to school is to laugh when disciplined and he does so, the teacher is probably going to be offended. Yet for the student, this is the appropriate way to deal with the situation. The recommended approach is simply to teach the student that he needs a set of rules that brings success in school and at work and a different set that brings success outside of school. So, for example, if an employee laughs at a boss when being disciplined, he will probably be fired.

Many of the greatest frustrations teachers and administrators have with students from poverty is related to knowledge of the hidden rules. These students simply do not know middle class hidden rules nor do most educators know the hidden rules of generational poverty.

To be successful, students must be given the opportunity to learn these rules. If they choose not to use them, that is their choice. But how can they make the choice if they don’t know the rules exist?

Relationships are Key

When individuals who made it out of poverty are interviewed, virtually all cite an individual who made a significant difference for them. Not only must the relationship be present, but tasks need to be referenced in terms of relationships.

For example, rather than talk about going to college, the conversation needs to be about how the learning will impact relationships. One teacher had this conversation with a 17-year-old student who didn’t do his math homework on positive and negative numbers.

"Well," she said, "I guess it will be all right with you when your friends cheat you at cards. You won’t know whether they’re cheating you or not because you don’t know positive and negative numbers, and they aren’t going to let you keep score, either. He then used a deck of cards to show her that he knew how to keep score. So she told him, "Then you know positive and negative numbers. I expect you to do your homework."

From that time on, he did his homework and kept an A average. The teacher simply couched the importance of the task according to the student’s relationships.

Conclusion

Students from generational poverty need direct teaching to build cognitive structures necessary for learning. The relationships that will motivate them need to be established. The hidden rules must be taught so they can choose the appropriate responses if they desire.

Students from poverty are no less capable or intelligent. They simply have not been mediated in the strategies or hidden rules that contribute to success in school and at work.

References

Feuerstein, Reuven, et al. (1980), Instrumental Enrichment: An Intervention Program for Cognitive Modifiability Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Joos, Martin. (1967) The Styles of the Five Clocks. Language and Cultural Diversity in American Education, 1972. Abrahams, R.D. and Troike, R.C., Eds. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Making Schools Work for Children in Poverty: A New Framework Prepared by the Commission on Chapter 1, (1992). Washington, DC: AASA, December

Montano-Harmon, Maria Rosario (1991). Discourse Features of Written Mexican Spanish: Current Research in Contrastive Rhetoric and its Implications. Hispania, Vol. 74, No. 2, May 417-425.

Montano-Harmon, Maria Rosario (1994). Presentation given to Harris County Department of Education on the topic of her research findings.

Wheatley, Margaret J. (1992). Leadership and the New Science. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Ruby K. Payne, Ph.D., founder and president of aha! Process, Inc. (1994), with more than 30 years' experience as a professional educator, has been sharing her insights about the impact of poverty – and how to help educators and other professionals work effectively with individuals from poverty – in more than a thousand workshop settings through North America, Canada, and Australia. More information can be found on her web site, www.ahaprocess.com.

Ruby K. Payne presents a Framework for Understanding Poverty, a two-day workshop, on her U.S. National Tour each year, and also has produced accompanying materials. Both are available on her website, www.ahaprocess.com. Also opt-in to aha’s email news list for the latest poverty and income statistics (free) and other updates.

aha! Process, Inc.

(800) 424-9484 (281) 426-5300

fax: (281) 426-5600

Recognizing an American Holocaust

Since the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, non-Indian America, asserted its cultural superiority by both assuming and asserting that Indians either must assimilate or blend into the American "melting-pot" and perish as a distinctive people or must gradually die off as their culture and skills fail to cope with the changes imposed on them by the advance of an allegedly superior white civilization. This asserted cultural superiority manifested into actual governmental policies affecting Native Americans, such as the General Allotment Act (GAA).

This article argues that the GAA and its effects constitute genocide. In arguing that the GAA constitutes genocide, this article further argues for a more liberal definition of genocide than the one in the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention). Congress passed the GAA as the next best answer to civilize Indians when federal policymakers determined that reservations failed in that purpose. The continued goal of assimilation by the GAA may not have succeeded, but it did destroy a way of life that by some constitute genocide.

This paper begins by discussing the affects of the GAA on Native American lives. Secondly, the paper will discuss the evolution of genocide’s definition and argue for a more liberal definition, so to include such destructive government sponsored policies as the GAA. Finally, the paper will demonstrate how the GAA constitutes genocide under the more liberal definition.

Manifest a Destiny While Destroying Another: The Effects of Allotment

Ironically, lawmakers passed the Dawes Act with the best of intentions to help the Indians, but the effects of the GAA hardly helped Indians in any positive way. The Removal and Reservation eras preceding Allotment virtually destroyed the many Indian nations’ way of life. The goals of the allotment and assimilation era were in many respects continuations of the reservation goals: agriculture, Christianity, and citizenship. The primary agent of civilization and citizenship was private land ownership. Advocates of the policy believed that individual ownership of property would turn the Indians from a savage, primitive, tribal way of life to a settled, agrarian, and civilized one. Assimilation was viewed as both humanitarian and inevitable. The cornerstone of this social engineering, this "legal cultural genocide," was the replacement of tribal communal ownership of land with private property. The GAA authorized the break up of the reservations. Indians were to receive allotments of land in severalty, and the remaining surplus lands were to be opened to settlement.