RETURN TO FIRST PAGE

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Colorado Measures of Academic Success

Lone Picketer Calls for Investigation of Colorado School Districts for Ignoring Decades-Old Native History Legislation

The Eclipse of the Sun:

Lack of American Indian Curriculum in

Certain Colorado

High Schools

Institutional Racism Poster

Better Dead Than Red, Kicked To The Curb Poster

By

Carol Harvey

Copyright May 25, 2021

Dedication

To the Indian Parent who stood up for minority students’ rights, as a matter of simple justice. A law existed that needed to be complied with for their well-being. The U.S. Civil Rights Commission noted in 2018 that the “lack of appropriate cultural awareness in school curriculum focusing on Native American history or culture” can (1) be harmful to American Indian students; (2) contribute to a negative learning environment; (3) trigger bullying; and (4) result in negative stereotypes across the board. The same is true for all minority students.

Acknowledgments

Family

Nobody has been more helpful to me in the pursuit of this project than the members of my family. They provided emotional support and made sure that whatever resources and assistance I needed for this project were available. Thank you to my most beloved husband (who made breakfast, lunch and dinner for me so I could focus on this project) whose love provides such joy and stability in my life.

For The Truth Tellers

Representative Evans’ motivation in The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States on the Indian Removal Act:

If I could stand up between the weak, the friendless, the deserted, and the strong arm of oppression, and successfully vindicate their rights, and shield them in their hour of adversity, I should have achieved honor enough to satisfy even an exorbitant ambition; and I should leave it as a legacy to my children, more valuable than uncounted gold — more honorable than imperial power.

Representative Evans, speaking on S. 102, on May 18, 1830, 21st Cong., 1st sess., Register of Debates in Congress 1049.

Symbolism of Photos in Posters

![]()

Institutional Racism, The White Man Has His Feet on the Neck of a Dead Indian, Proudly Proclaiming His Victory in Crushing the Indian as the Macabre Ghouls in the Background Screech and Cackle

Institutional racism has a life of its own. It does not need to be perpetuated - it is, by definition as being institutionalized, self-perpetuating. It no longer needs to find a host to propagate; it is airborne.

“Institutional racism is often the most difficult to recognize and counter, particularly when it is perpetrated by institutions and governments who do not view themselves as racist. When present in a range of social contexts, this form of racism reinforces the disadvantage already experienced by some members of the community. For example, racism experienced by students at school may result in early school dropout and lower educational outcomes. Together with discrimination in employment, this may lead to fewer employment opportunities and higher levels of unemployment for these students when they leave school. In turn, lower income levels combined with discrimination in the provision of goods and services restrict access to housing, health care and life opportunities generally. In this way, institutional racism may be particularly damaging for minority groups and further restrict their access to services and participation in society.” See www:racismnoway.com.au/classroom/Factsheet/32.html.

Better Dead Than Red (Top of Poster)

We have internalized the European-American genocidal message Better Dead Than Red. We no longer need to be killed; we are killing ourselves and each other. The circumstances of our lives are causing serious bodily and mental harm, calculated to bring about our physical destruction in whole or in part, the continuation of our genocide.

Kicked to the Curb (Bottom of Poster)

American Indians have been kicked to the curb.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART 1: Introduction

PART 2: History of § 22-1-104

History of § 22-1-104

Colorado House Bill 19-1192

Colorado School Districts and § 22-1-104

Internet Cites Stating § 22-1-104 Is in Force and Effect

PART 3: U.S. Civil Rights Commission Reports Lack of American Indian Curriculum Can (1) Be Harmful to American Indian Students; (2) Be Isolating and Limiting; (3) Contribute to a Negative Learning Environment; (4) Trigger Bullying; and (5) Result in Negative Stereotypes Across the Board; Auditing Federal Funding; President Obama’s Executive Order; Cultural Imperialism; and Colorado’s Durango 9-R Board of Education January 2021 Resolution Apologizing for Inequities

Awareness of Need for Relevant American Indian Curricular Instruction Goes Back to 1928

Federal Funding to Serve American Indian Students; Need for Auditing

Improving American Indian and Alaska Native Educational Opportunities and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities

Cultural Imperialism

Colorado’s Durango 9-R Board of Education January 2021 Resolution Apologizing for Failure to Provide “Equitable Educational Opportunities”

PART 4: Federal Education Funding to State of Colorado

PART 5: Colorado Education Associations

Colorado Education Association Supports C.R.S. § § 22-1-104 (1)-(6) (aka HB 19-1192)

Colorado Association of School Boards (“CASB”) Legal Opinion on § 22-1-104

CASB’s Policy on Graduation Requirements - Recommended Language for CO School Districts that Best Meets Intent of Law, includes § 22-1-104(2) Civics Course

CASB, Colorado Association of School Executives (“CASE”) and Colorado Education Association (“CEA”) Joint Influence over Legislature and CO DOE

PART 6: Brief History of American Indian Education

Troubling Legacy

Kennedy Report in 1969: Non-Indian Teachers and Children Misunderstand Indian Culture and History

National Congress of American Indians Report: Erasure from Education Fuels Harmful Biases

Contemporary Stereotypes Regarding Indians: Rick Santorum

PART 7: Colorado Academic Standards: History and Development

1998 Colorado Model Content Standards for Civics

2009 Civics Standards for High School

2013 Colorado's District Sample Curriculum Project

2020 Civics Standards for High School; 2020 Civics Standards for High School: Address Indian History, Culture and Social Contributions by Merely Inserting Word “Tribal” Wherever List of Governmental Entities Occurred

State of State Standards for Civics and U.S. History in 2021; Colorado Receives Grade of ‘D’

2021 SB 21-067 Civics Standards to Be Developed As Soon As Is Practicable

CCSD’s Social Studies Curricular Resource Review Implementation Scheduled for 2024-2025

PART 8: Holocaust and Genocide Education in Colorado Public Schools

PART 9: Community Concerns with Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Indigenous Community Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

CCSD’s Students’ Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Denver’s Public School’s Black Students Concerned with Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Other Minorities Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

African-American Community Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Asian-American Community Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Latin Community Concerned with Need for More Inclusive Curriculum Statewide

LGBTQ Community Concerned with Need for More Inclusive Curriculum Statewide

Site after Site on the Internet Proclaim Colorado Law Mandating LGBTQ Inclusion in Curriculum

White Community Divided Over Need for More Inclusive Curriculum

Need for Civics Education in Tumultuous Time of Polarization

PART 10: Curriculum Review with Racial and Cultural Relevance Focus

CCSD’s Superintendent Email Message to Parents on April 23, 2021 regarding Curriculum Review with Racial and Cultural Relevance Focus

CCSD’s Parents’ Respond to Superintendent Siegfried’s Email Message to Parents on CCSD Curriculum Review with Racial and Cultural Relevance Focus

Critical Race Theory

CCSD’s Media Response to Parents’ Concerns at CCSD BOE Meeting regarding Curriculum Review with Racial and Cultural Relevance Focus

CCSD’s Social Studies Curricular Resource Review Implementation Scheduled for 2024-2025

June 23, 2021 CCSD BOE Meeting: CCSD’s Curriculum Review Process

CCSD’S Curriculum Development Process Not in Compliance with § 22-1-104

August 9, 2021, CCSD BOE Meeting

PART 11: Investigation of Colorado Public School Districts, including Cherry Creek School District, to Determine if There Is a Countenanced, Systemic Violation by High Schools of § 22-1-104, C.R.S.

Petition for Investigation of Colorado Public School Districts, including Cherry Creek School District, to Determine if There Is a Countenanced, Systemic Violation by High Schools of § 22-1-104, C.R.S.

Protest Commenced August 19, 2021

New Mexico Federal Case - Yazzie-Martinez v. State Of New Mexico: State’s Public Education Department Failed to Provide Native American, Hispanic and Other Students from Diverse Populations a Sufficient Education Due in Part to Lack of Culturally and Linguistically Relevant Curriculum

Protest Press Release, August 19, 2021

PART 12: Grant of Authority to Colorado Board of Education and School Districts

Colorado Constitution Grant of Authority to Colorado Board of Education and School Districts

Colorado Legislation Requiring CO DOE to Adopt Academic Standards (CRS § 22‐2‐106, State Board - Duties – Rules)

Standards in Colorado Legislative Enactments

Colorado Legislation Requiring CO DOE to Adopt Graduation Guidelines (CRS § 22‐2‐106, State Board - Duties – Rules)

CO DOE Purpose of Graduation Guidelines

2020 CO DOE Social Studies Standards Compliance Required

New Statute 22-7-1005, C.R.S. Requires CO DOE to Revise Social Sciences Standards on or before July 1, 2022

PART 13: Colorado High School Diplomas

Academic Degrees Certify Student’s Achievement

Revocation of Diplomas

Tainted Diplomas

CO DOE Monitors School District Compliance with Graduation Guidelines Under an Honor System

CO DOE Enforcement of State Graduation Guidelines

Loss of Accreditation for Failure to Comply with Statutory and Regulatory Requirements

PART 14: Judicial Review of § 22-1-104

Colorado Attorney General Opinion on § 22-1-104

Colorado Appellate Court Decision on § 22-1-104

Colorado Federal District Court, Lane v. Owens, 2003 Cited § 22-1-104 in Dicta as Valid Example of Curriculum Requirement

Colorado Supreme Court Decision regarding Use of Term “Must” by General Assembly (aka State Legislature)

PART 15: CO DOE Consistency in Requiring Compliance with § 22-1-104

CO DOE Consistency in Requiring Compliance with § 22-1-104 pursuant to Colorado Law Entitled to Judicial Deference

CO DOE Enforcement of State Graduation Guidelines

PART 16: CCSD BOE References to § 22-1-104

CCSD BOE References to § 22-1-104 Date Back to 1996

CCSD Administration’s Confirmation of Obligatory Status of § 22-1-104

CCSD’s Social Studies Curriculum

PART 17: CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence (“OIE”) Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (“P.A.S.S”.) Indigenous Parent Action Committee (“IPAC”) Meetings

CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence (“OIE”) Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) September 16, 2020 Goals

P.A.S.S. IPAC Meetings

October 27, 2020 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence (“OIE”) Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

November 18, 2020 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

November 19, 2020 IPAC Member Letter to Superintendent re Compliance with § 22-1-104; Letter re Community Forum

November 19, 2020 IPAC Member CORA Request to CCSD

December 8, 2020 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

December 5, 2020 CCSD’s OIE Willing to Discuss § 22-1-104 with IPAC Member

December 10, 2020 CCSD’s CORA Response to IPAC Member

January 12, 2021 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

February 10, 2021 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

February 17, 2021 CCSD’s Office of Inclusive Excellence Partnerships for Academically Successful Students (P.A.S.S.) IPAC Public Meeting

March 26, 2021, IPAC Member Second CORA Request

March 31, 2021, CCSD - No Timeframe in § 22-1-104 for Compliance

April 2, 2021, CCSD CORA Response – Ten Links to Web Sites

May 2021, IPAC Member Meeting with CCSD

PART 18: Current Implementation of § 22-1104 by Colorado Public School Districts

Current Implementation of § 22-1104

Poudre School District Response to HB 19-1192

PSD Social Studies

Jefferson County’s School District Board of Education (“Jeffco”) Updated Civics Curriculum in February 2020

PART 19: History, Culture, Social Contributions and Civil Commission and Other Provisions of § 22-1-104

History, Culture, Social Contributions and Civil Commission

School Districts to Hold Community Forums

Amendment of § 22-1-104 to Detail Civics Instructional Requirements

PART 20: American Indian Presence and History in Colorado

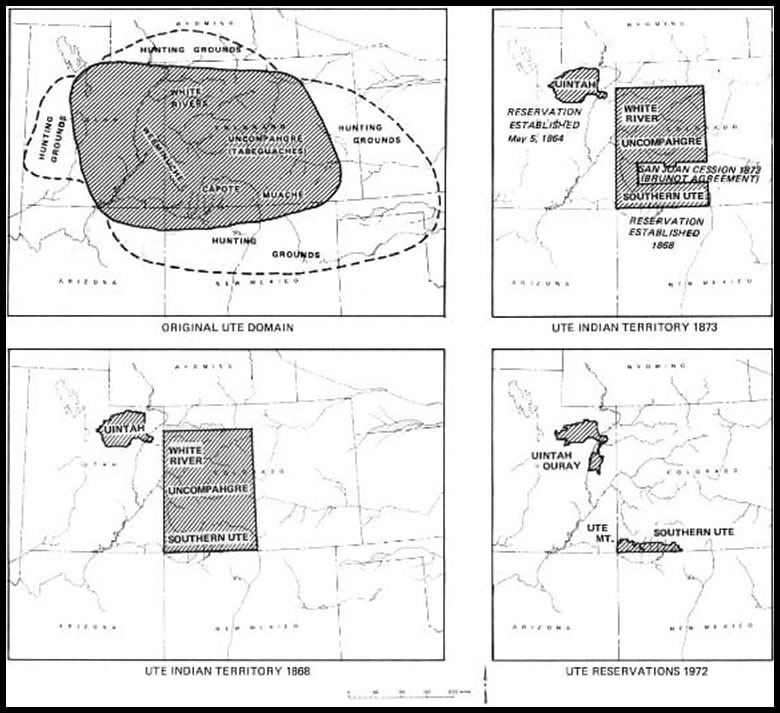

American Indian Presence in Colorado

Denver City Council Land Acknowledgement

PART 21: Negative Academic Performance of AI/AN Students in Colorado; Disciplinary Rates of AI/AN Students in CCSD

Indians Entitled to State Public Education

Staggering Negative Academic Performance of AI/AN Students in Colorado

CO DOE Press Release, August 2020, Building Cultural Awareness in Support of American Indian/Alaska Native Students

2011 Colorado Campaign to Boost American Indian Graduation Rates

“Native Groups Urge Education Parity,” Indian Country Today Article, Original May 7, 2011, Updated Sep. 13, 2018

School-to-Prison Pipeline

Minority Student Disciplinary Rates in Cherry Creek School District 2017-2020

Colorado’s Office of the Child’s Representative - Legal Representation to Children Involved in Colorado Court System

School Justice Roundtable Hosted by Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser

PART 22: Brief Review of Indian History Policy

Brief Review of Indian History Policy

Stereotypical View of Indians Expressed at Highest Levels of Government

Extermination, Extinction or Starvation for Indians

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Nov. 26, 1855: Indians Would Either Be Exterminated by Whites or Become Extinct

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Nov. 6, 1858: Allow Indians to Starve or Exterminate Them

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Nov. 1859: Gold Discoveries in Colorado; United States Deprived Indians of Any Means of Subsistence in Colorado

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Oct. 1863: Ute Cession to United States of Arable Land and Mining Districts in Colorado

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1864, Colorado Superintendency: Cheyennes and Arapahoes Want Peace; Military Says Further Chastisement Needed; Sand Creek Massacre

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1865: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Total Destruction of Indians; Whip Cheyennes; Major Wyncoop with Chiefs of Tribes Under His Charge Met with Governor Evans, Colorado, Seeking Peace; Arapahoe and Cheyenne Indians who Escaped from Sand Creek Massacre - Left Almost Helpless in Dead of Winter; Treaty with Arapahoes - No Money, No Specific Land; Commissioners Negotiating with Arapahoes for Treaty – Hard, Mean-Spirited, Sharp Negotiating Tactics Used by U.S., Give Land with Game and Arable Land, Not Gold and Silver

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1866: Treaty with Utes – Gold, Silver and Coal Discovered on Their Land

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1877: Proposal to Remove Indians in Colorado and Arizona to Facilitate Gold and Silver Mining and Farming by Whites

Relocation Program Effect on Colorado

PART 23: American Indian Education

2021 Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

Conversion to Christianity and Education Seen as Solution

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1877: Kill the Indian in Him and Save the Man

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1887: Progress toward Civilization includes Education

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1894: Education to Convert Indians into American Citizens; Education Should Seek Disintegration of Tribes; Inculcate U.S. Patriotism; Indians to Attend Public Schools

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1899: Education Turned from Tepee, Chase and Barbaric Savage Life to Civilization

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1901: Get Students by Cajolery, Threats, Bribery, Fraud, Persuasion or Force

Meriam Report, Boarding Schools Inadequate

PART 24: Conclusion

Pall of Orthodoxy v. Academic Freedom

Obligatory Status of § 22-1-104

Action Required

Denver Public School District

Denver Public High School Graduation Requirements - No Reference to § 22-1-104

Denver East High School

Denver West High School

Denver North High School

Denver South High School

Backlash of Structural Racism Being Felt in the American Indian Community

Federal Government Assistance Needed

Investigation of Federal Funding Given to Colorado for American Indian Students

CCSD Indigenous Parent Action Committee Meeting, August 26, 2021, ESSER and State Funds

US DOE Proposed Priorities American History and Civics Education

Appendix

Appendix 1: Presentation on § 22-1-104, February 17, 2021, Let Indigenous Voices Be Heard Panel

PART 1: Introduction

High school curriculum equity issues are a hot topic in Colorado. The Cherry Creek School District (“CCSD”) Board of Education (“CCSD BOE”) meeting on June 23, 2021, evidences the importance of this issue. Almost two hundred people attended the meeting to discuss curriculum revision – the Board meeting room was filled to capacity; an overflow room was opened and it was filled to capacity with people sitting on the floor. More people were outside of the facility watching the meeting online. About a dozen men from an extremist militia group stood guard at the entryway to the meeting, armed with, at a minimum visually, pepper spray.1

Over one hundred people registered to speak at the meeting, where they were each allotted three minutes. The meeting went on into the early morning of June 24, 2021. An overwhelming majority of the one hundred speakers at the meeting were in support of a culturally responsive curriculum for all students. There were others at the meeting who argued that it is a part of critical race theory.

The CCSD BOE clearly stated in the meeting that Cherry Creek Schools have not and are not adopting the Critical Race Theory. According to Cherry Creek district officials, Critical Race Theory is a theoretical framework, not a curriculum.

After the meeting, Cherry Creek Education Association president and middle school science teacher Kasey Ellis said:

“We want to thank the Cherry Creek School District for their continued work on equity within the district and look forward to continuing to work with them on this. No matter our color, background or zip code, we want our kids to have an education that imparts honesty about who we are, integrity in how we treat others, and courage to do what’s right. But there are those who are now stoking fears about our schools, trying to dictate what teachers say and block kids from learning our shared stories of confronting injustice to build a more perfect union. They push for outdated and inaccurate lessons, redlining the realities of our history in order to justify the harms of our present. What a good teacher knows is we can’t just avoid or lie our way through our challenges; we must find age-appropriate ways to tell hard truths about our country’s past and present in order to prepare our kids to create a better future.”2

What led to this significant meeting on June 23, 2021, was a growing consensus among minorities that the CCSD needed a more inclusive curriculum and one Indian parent’s (hereinafter “Indian Parent”) pursuit of justice for all minority students.

The subsequent meeting on August 9, 2021, continued the discussion of the need for an inclusive curriculum and compliance with § 22-1-104, C.R.S., as well as opposition to it:

Max Gimelshteyn, a father of two, said, “I’m here to voice the concerns of hundreds of parents that were not able to get on the list to speak tonight…The assertion that the school is simply trying to teach history better is frankly disingenuous and I think anybody doing it is probably aware of that…The so-called cultural response education that is being implemented in K through 12 education often violates the First Amendment and civil rights because it is not being taught as a theory, which would normally require a subject to be analyzed, scrutinized and debate. Instead, it’s being practiced as ideology, attempting to coerce children into a certain belief system. It violates First Amendment rights because our government cannot compel…students to profess political, religious or ideological beliefs.

Jamie Logan, a CCSD teacher and a parent, said … “We love your kids. We love every student…I promise you that I haven’t been spending all summer creating this evil plan to indoctrinate your child with self-loathing and hatred…These claims are laughable…It’s not what we do.” She continued, “Please respect my profession. You teach your kids values in your home and I get to teach your kids to be critical thinkers, ask questions, be curious, collaborate…We will be talking about race in school. It’s really hard. I get it.”3

NOTES

1. https://villagerpublishing.com/parents-speak-out-to-the-cherry-creek-school-board/ (accessed online May 5, 2021).

2. https://kdvr.com/news/local/cherry-creek-schools-hotly-debates-critical-race-theory-how-history-should-be-taught/ (accessed online May 5, 2021).

3. Public Speaks Its Mind At Cherry Creek School Board Meeting, Again, August 18, 2021, Freda Miklin

https://villagerpublishing.com/public-speaks-its-mind-at-cherry-creek-school-board-meeting-again/ (accessed online August 25, 2021).

PART 2: History of § 22-1-104

In 1973, the Colorado state legislature enacted §123-21-4, C.R.S, requiring public schools to teach about the history and culture of Spanish-Americans and American Negroes.1

While legislation was introduced in 1992 in an attempt to make it optional, it failed to pass (SB 108).2

In 1998, it was amended to include American Indians at the urging of Comanche State Representative Suzanne Williams (HB 98-1186, enacted 4/17/1998).3 Fast-forward twenty-three years and the Indian community has yet to see former Representative and Senator Williams’ state legislative lobbying effort to get HB 98-1186 passed being fulfilled.

In 2003, the legislature mandated that students must satisfactorily complete a course on the civil government of the United States and the state of Colorado, as a condition of high school graduation, which expressly included the history and culture of certain minorities, effective with the graduating class of 2007 (SB 36, enacted 4/22/2003).4 The minorities included African-Americans, American Indians and Latinos.

In May 2019, teaching regarding Asian Americans and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals within these minority groups and the contributions and persecution of religious minorities were added to the statute (HB 19-1192, enacted 5/28/2019).5

On April 29, 2021, it was further amended by SB 21-067 to address specific topics under federal and state constitutions and governments.6

Colorado House Bill 19-1192

On May 28, 2019, Colorado House Bill 19-1192 (“HB 19-1192”) (codified as § 22-1-104, C.R.S.) was passed by the Colorado state legislature, addressing the need for an inclusive curriculum in the state’s public schools. It specifically became effective immediately. It provides as follows:

22-1-104. Teaching of history, culture, and civil government.

The history and civil government of the United States and of the state of Colorado, which includes the history, culture, and social contributions of minorities, including, but not limited to, American Indians, Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans, the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals within these minority groups, and the intersectionality of significant social and cultural features within these communities, and the contributions and persecution of religious minorities, must be taught in all the public schools of the state.

HB 19-1192 was introduced by Rep. Gonzales-Gutierrez, a granddaughter of Denver activist Rudolfo “Corky” Gonzales, a leader in the Crusade for Justice group. While a senior at Denver’s West High School in 1969, Rep. Gonzales-Gutierrez’s mother participated in protests on March 20-21, 1969. One grievance was the lack of Chicano curriculum. Students from Manuel, Thomas Jefferson, Lincoln and South High Schools, all came out and supported the students at West High School. The protests came to be known as the “blowouts.” Numerous arrests occurred in what the demonstrators had hoped would be a non-violent presentation of their grievances to school administrators.

As reported by CPR News,

The West blowouts helped kick-start what became known as El Movimiento, the Chicano Movement. Just a few weeks later, the Crusade for Justice held the first ever Youth Liberation Conference. Nearly 1,500 young Chicanos from across the country were drawn to Denver.7

In a symbolic ceremony, Governor Jared Polis signed HB 19-1192 at Denver’s Rudolfo “Corky” Gonzales Branch Library. Rep. Gonzales-Gutierrez stated: “Our diversity is what makes our country and our state strong, but for too long, individuals and communities that have moved or immigrated here and those that have been here for many centuries ... have been excluded from our teaching of history.” Three generations later, one Latino family seeking an inclusive curriculum has yet to see the fruition of its activism.8

Colorado School Districts and § 22-1-104

In researching school districts in Colorado, there is not much discussion regarding § 22-1-104. It is uncertain how many, if any, Colorado school districts have a civil government course complying with § 22-1-104. A Google search only turned up the Cherry Creek, Jefferson County and the Poudre School Districts. It would seem Jefferson County is the only district that is in compliance with § 22-1-104.9 Also, even though the state legislature in 2003 made the completion of a course including these subjects a condition of graduation, school districts are willfully ignoring § 22-1-104. Students receive diplomas even if they have not been offered or satisfactorily completed the course required under § 22-1-104.

The Colorado Early Colleges Board of Directors has established the following graduation requirements for all students pursuing graduation. All of the following criteria must be met in order for a student to graduate:

*Social Science credit includes the satisfactory completion of a civics/government course that encompasses information on both the United States and State of Colorado (C.R.S 22-1-104).10

Internet Cites Stating § 22-1-104 Is in Force and Effect

Various internet cites state § 22-1-104 is in force and effect in Colorado when this is false. It raises a question regarding the integrity of the state and deceptive advertising.11

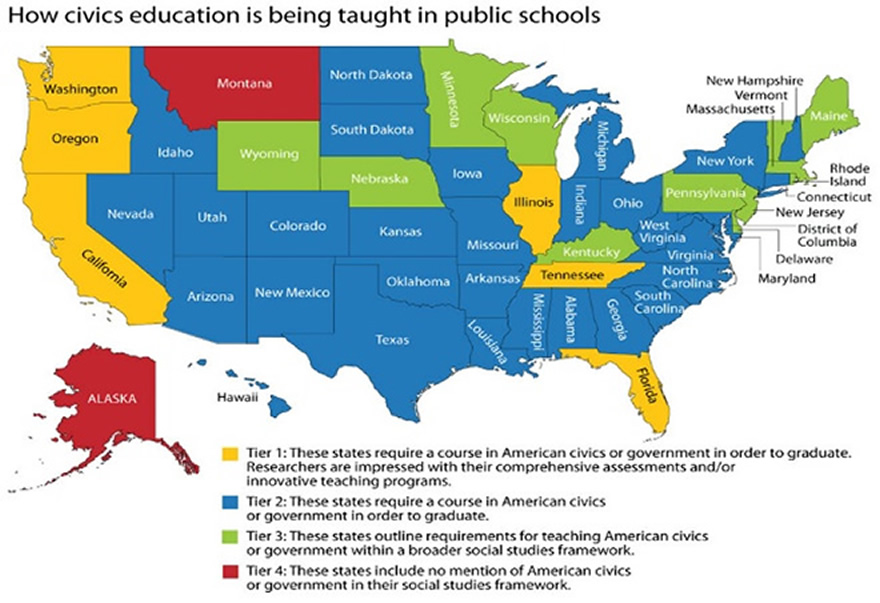

https://www.csmonitor.com/Media/Content/2018/0323/0323-civics-map

“Colorado in particular has one of the most robust civics education requirements in the country. In fact, the only statewide graduation requirement in Colorado is the completion of a civics and government course. Colorado designed curriculum for a full year civics course, and provides a myriad of resources and guidance for teachers on the subject.” https://populationeducation.org/an-essential-guide-to-civics-education-in-the-united-states-today/

Education Commission of the States

Colorado: Public schools are required to teach a course on the history and civil government of the state of Colorado and the United States, to include the history, culture and contributions of minorities. Satisfactory completion of this course is required for high school graduation. C.R.S. 22-1-104

NOTES

1. §123-21-4, C.R.S, 1973

2. 1992 SB 108

3. 1998 HB 1186

4. 2003 SB 36

5. 2019 HB 19-1192

6. 2021 SB 21-067

7. https://www.cpr.org/2019/03/18/chicano-progress-today-owes-much-to-the-denver-west-high-blowouts-of-50-years-ago/ (accessed online March 1, 2021).

8. www.coloradopolitics.com/news/colorado-schools-to-teach-a-far-more-inclusive-version-of-history/article_07619028-8195-11e9-9f1a-63bd85281cbd.html (accessed online March 5, 2021).

9. https://www.thepulsefromcandi.com/blog/category/socialstudies

(accessed online August 20, 2021).

10. https://coloradoearlycolleges.org/wp-content/uploads/CEC_Files/CEC_Fort_Collins/Documents_Forms/FC_HS_and_Westminster/Graduation_Requirements_FC.pdf (accessed online January 5, 2021).

11. https://www.csmonitor.com/Media/Content/2018/0323/0323-civics-map (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://populationeducation.org/an-essential-guide-to-civics-education-in-the-united-states-today/ (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://ecs.secure.force.com/mbdata/MBQuest2RTANW?Rep=CIP1601S (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2018/02/21/446857/state-civics-education/ (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://www.aft.org/ae/summer2018/shapiro_brown (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://medium.com/generation-citizen/mapping-the-civic-education-policy-landscape-9e5766692efe (accessed online March 5, 2021).

https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/data-most-states-require-history-but-not-civics (accessed online March 5, 2021).

PART 3: U.S. Civil Rights Commission Reports Lack of American Indian Curriculum Can (1) Be Harmful to American Indian Students; (2) Be Isolating and Limiting; (3) Contribute to a Negative Learning Environment; (4) Trigger Bullying; and (5) Result in Negative Stereotypes Across the Board; President Obama’s Executive Order; Cultural Imperialism; and Colorado’s Durango 9-R Board of Education January 2021 Resolution Apologizing for Inequities

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission in its December 2018 Report “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans” found that “Today, the vast majority of Native American students attend public schools operated by state and local authorities.”1

They determined that:

In addition, for Native American students learning in schools without historically accurate representation or discussion of Native American people in curriculum, the educational experience can be isolating and limiting. The lack of accurate and culturally inclusive curriculum on Native Americans also limits the ability of all students to understand and be aware of the history and contributions of Native Americans.2

Specifically:

A lack of appropriate cultural awareness in school curriculum focusing on Native American history or culture also raises concerns. …

The White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education heard concerns that curricula surrounding Native American history or culture may be irrelevant or inaccurate, and may sometimes use inappropriate Native American clothing, songs, dances, customs, and arts, which can potentially have harmful effects on Native American students. Moreover, the White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education found that this can contribute to a negative learning environment, as Native students may be confronted with misinformation that they may feel compelled to correct, which can cause uncomfortable and difficult situations, and can possibly trigger bullying.

Recent national public opinion polling also shows that lack of accurate history about Native Americans in U.S. public education may contribute to negative stereotypes across the board.3

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission recommended “grant funding to develop curricula and lesson guides that state and local school districts may then choose to adopt to maximize instruction that includes non-derogatory, culturally inclusive discussion of Native American history and student experience.”4

Federal Funding to Serve American Indian Students: Need for Auditing

The majority of K-12 schools in the U.S. receive a combination of funds from local, state, and federal funding streams.5 Title VI of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) provides grants to support schools and school programs that serve Native American students. 20 U.S.C. §§ 7421–7429.6

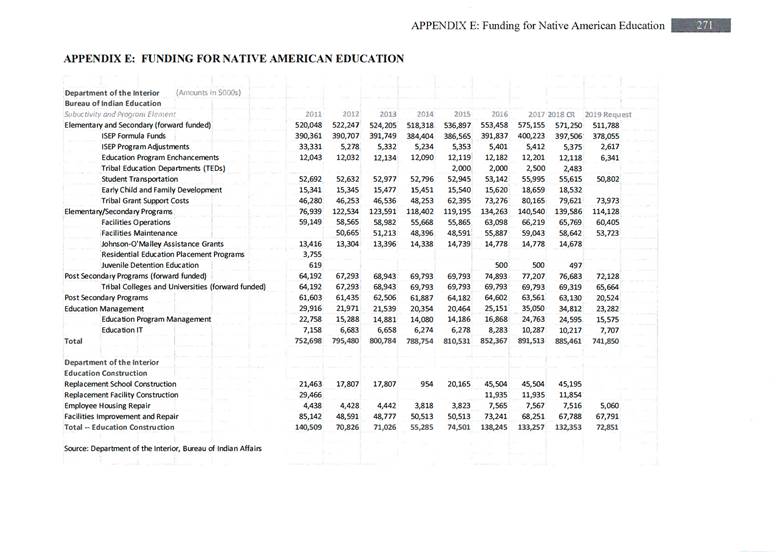

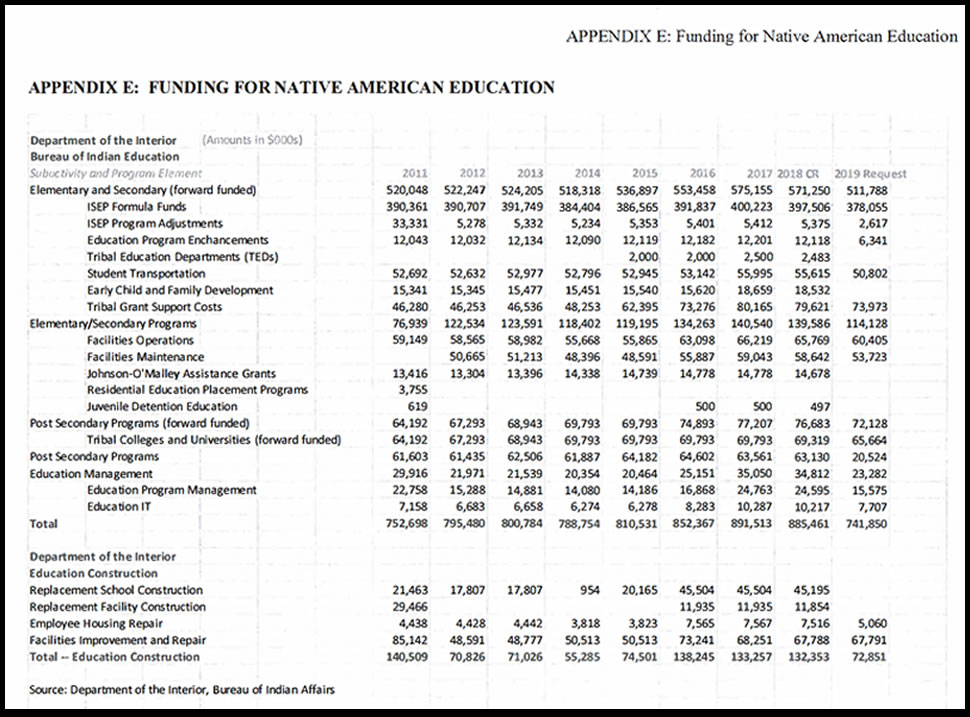

The Chart below documents Funding for Native American Education:7

If Colorado is receiving any of this funding, it is obligated to address American Indian student needs, including the “lack of appropriate cultural awareness in school curriculum focusing on Native American history or culture” given the Findings of the Commission that this omission can (1) be harmful to American Indian students; (2) contribute to a negative learning environment; (3) trigger bullying; and (4) result in negative stereotypes across the board.

The need for auditing how Indian federal funds are spent can be seen in the National Advisory Council on Indian Education (“NACIE”) caution. NACIE was concerned that “Title VI funds go specifically toward the Indian students and tribal communities for whom they are intended and that services continue to target the unique, culturally related academic needs of [American Indian/Alaskan Native] (“AIAN”) students. NACIE is concerned that budgeted and unfilled vacancies at the U.S. Department of Education (“ED”) and Office of Indian Education (“OIE”) have reduced the capacity to monitor all ESEA* grant programs to ensure that Title funds are spent appropriately.” 8

* Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA) as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), 20 U.S.C. §7471.

When signed into law in 2015, ESSA further advanced equity in U.S. education policy by upholding important protections outlined in “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB). At the same time, it granted flexibility to states in exchange for rigorous and comprehensive state-developed plans designed to close achievement gaps, increase equity, improve the quality of instruction, and increase outcomes for all students. 9

For example, the State of New Mexico details its allocation of Indian education funds as shown in the chart below:10

Awareness of Need for Relevant American Indian Curricular Instruction Goes Back to 1928

The tragic situation confronting American Indian students is compounded by the fact that as far as the Meriam Report in 1928, the importance of curriculum has been reiterated.

In 2009, W. Journell, wrote the article, “An incomplete history: Representation of American Indians in State Social Studies,” analyzing difficulties with the representation of American Indians in social studies classes:

Nowhere do definitions of the traditional curriculum resonate louder than with the depiction of American Indians and Alaska Natives in public school classrooms. Studies have shown that students enter public education conceptualizing American Indians as warlike, half-naked savages, a depiction stemming from cartoons and Hollywood productions. Although the educational process begins to sophisticate students' understanding of American Indians rather quickly, research shows that students' knowledge of American Indian culture plateaus around fifth grade when discussions of American history tum to the American Revolution and the subsequent rise of the American nation (Brophy, 1999). From that point forward, researchers found that American Indians "disappeared or were mentioned only as faceless impediments to western expansion" (p. 42).11

Ogbu (1987, 1992) contends that members of minority groups need to feel as if they are positively represented in curricula in order to become engaged in their education. He argues that this is particularly important for what he terms "involuntary minorities," groups that were either forcibly brought to the United States or systematically oppressed by Europeans, such as African Americans and American Indians. In order for members of those groups to embrace public schooling, they must see examples of people like themselves within the curriculum, which often does not occur with traditional forms of social studies education. Moreover, when members of minority groups are mentioned within the curriculum it is often to remind students of periods in history when a particular group was discriminated against and then to celebrate their subsequent struggle for equality. This practice raises an important question regarding the representation of marginalized groups in American history; should members of minority groups be included within the curriculum as exemplars of people who fought for liberation against their oppressors, or as productive members of society that have contributed to the social, political, and economic fabric of our nation? (Epstein, 1998).12

Improving American Indian and Alaska Native Educational Opportunities and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities

On December 2, 2011, President Obama signed Executive Order 13592 — Improving American Indian and Alaska Native Educational Opportunities and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities, recognizing the unique political and legal relationship the United States has with the federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) tribes across the country, as set forth in the Constitution of the United States, treaties, Executive Orders, and court decisions.

For centuries, the Federal Government’s relationship with these tribes has been guided by a trust responsibility a long standing commitment on the part of our Government to protect the unique rights and ensure the well-being of our Nation’s tribes, while respecting their tribal sovereignty. In recognition of that special commitment and in fulfillment of the solemn obligations it entails Federal agencies must help improve educational opportunities provided to all AI/AN students, including students attending public schools in cities and in rural areas. … This is an urgent need. Recent studies show that AI/AN students are dropping out of school at an alarming rate, that our Nation has made little or no progress in closing the achievement gap between AI/AN students and their non-AI/AN student counterparts, and that many Native languages are on the verge of extinction. 13

Cultural Imperialism

In 2014, Donna Martinez, Ph.D., with the University of Colorado at Denver wrote the article, “School Culture and American Indian Educational Outcomes,” repeating the educational problems confronting American Indian students in Colorado. While the quotes are lengthy, it is important to capture her analysis.

American Indian students have the lowest educational attainment rates of any group in the United States. Many American Indian students perceive their current classroom experiences as unrelated to them culturally. 14

Insisting that the culture of school is more important than culture of students’ homes is form of cultural imperialism. Educational institutions believe that they offer a “culture blind” education to all American students; an education where race and cultural backgrounds of students do not matter, a reportedly culture-free zone.15

The idea of cultural blindness masks entrenched inequality. Educators assume that racial harmony is the norm in cultureless classrooms. Many view the underperformance of American Indian students in education as merely representing the lack of individual hard work and determination. Current educational disparities are viewed as a reflection of individual underachievement and lack of educational potential.16

A continuing educational gap in access to higher education, in a knowledge-based economy affects the socio-economic status of families and tribes. Many American Indian families depend on public education as a pathway to upward mobility and increased opportunities. Reservations remain economically underdeveloped, and the full potential of many American Indian students, untapped.17

Both Gallup and Kaiser Family polling data indicate that the majority of white Americans believe that racial discrimination no longer exists, that we live in a post-racial, color-blind, or race neutral society (Gallagher, 2012). The myth of color and cultural blindness maintains white privilege by negating the reality of racial and cultural inequality that American Indians face in American institutions.18

A 2012 ASHE report attributes American Indian attrition rates to the lack of representation of American Indians in curriculum and among teachers (McKinney, 2012). A U.S. Department of Education study identified the top reasons why American Indian students drop out of school: (1) uncaring teachers, (2) curriculum designed for mainstream America, and (3) tracking into low achieving classes and groups (Department of Education, 1991).19

An analysis of social studies curriculum found that American Indians are largely depicted as victims, rather than recognized for their contributions to American culture (Journell, 2009). Any American Indian history that is covered in schools focuses on a limited time frame of pre-twentieth century history. Contemporary achievements of tribal self-determination are excluded from school curriculums, as well as a substantial pre-Columbian history of ancient civilizations in America. This serves to reinforce media images of American Indians as people who existed in the past. Americans can feel as though they have accepted people who only existed in the past (Willow, 2010). Nearly all states cease their coverage of American Indians after wars in 1860s, creating an incomplete narrative. This creates significant implications for the historical consciousness of all students, and especially for American Indian students.20

While some states have passed legislation to support teaching about Americans Indians, no funding to support culturally relevant curriculum changes or teacher training accompany these measures. American Indians have struggled to gain a presence in educational curriculum. In the 1990s, a political “culture war” occurred in the United States regarding the presentation of public school history curriculum. Liberals asserted that a critical reading of national history needed to be presented; while conservatives felt that a celebration of “traditional” American historical accounts should be stressed. National educational standards, developed in 1994, did not expand the presence of American Indians in school curriculum.21

The Department of Education Indian Nations at Risk Task Force identified top priorities as the need for culturally and linguistically based education, and the need to train more American Indian teachers (Locke, 2007). 22

Colorado’s Durango 9-R Board of Education January 2021 Resolution Apologizing for Failure to Provide “Equitable Educational Opportunities”

Colorado’s Durango 9-R Board of Education in January 2021 passed a resolution apologizing for what they claim is a failure to identify and address “diversity, equity and inclusion” across the district in a “systemic” way. The resolution further says the district has failed to provide those students “equitable educational opportunities in a safe and healthy environment.” 23

Excerpt from Resolution:

WHEREAS, the District currently includes culturally diverse students, families, and staff representing many countries and territories, including approximately 21% of students who are Latino, 6% who are American Indian or Alaska Natives, 1% who are African American, and 1% who are Asian;

WHEREAS, the District acknowledges the presence of harmful injustices that extensive research has shown to exist at the intersections of race, class, religion, gender, sexuality, and abilities; and

WHEREAS, the District, despite past efforts, continues to have significant opportunity gaps as evidenced by disproportionate rates of discipline, drop-out, and achievement among various subpopulations;

NOTES

1. U.S. Civil Rights Commission in its December 2018 Report “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans, p. 221.

2. Ibid., pp. 221-222.

3. Ibid., p. 121.

4. Ibid., p. 222.

5. Ibid., p. 121.

6. Ibid., p. 122.

7. Ibid., p. 271.

8. The State of New Mexico 2019–2020 Tribal Education Status Report Issued November 2020, p. 51.

9. https://www.casb.org/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-misuse-of-crt (accessed online March 1, 2021).

10. Annual Report to Congress 2019-2020 National Advisory Council on Indian Education (NACIE) December 18, 2020, p. 13.

11. Journell, W. (2009). An incomplete history: Representation of American Indians in State Social Studies. Journal of American Native Indian Education. Retrieved from http://jaie.asu.edu/v48/index.html, p. 20 (accessed online March 1, 2021).

12. Ibid., p. 21.

13. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/12/02/executive-order-13592-improving-american-indian-and-alaska-native-educat (accessed online March 1, 2021).

14. Donna Martinez, “School Culture and American Indian Educational Outcomes,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 116 ( 2014 ), 199. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260758836_School_Culture_and_American_Indian_Educational_Outcomes (accessed online March 1, 2021).

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., 200.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid., 201.

20. Ibid., 202.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. https://pagetwo.completecolorado.com/2021/07/29/durango-school-board-apologizes-for-racism-cant-point-to-any-instances-of-discrimination/ (accessed online September 6, 2021).

PART 4: Federal Education Funding to State of Colorado

Under various federal programs, the state of Colorado files applications to receive funding. They must comply with the funding requirements. One example for Colorado is its Report for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (“IDEA”) funding. The IDEA funding the state receives is second in amount of monies received from the federal government. Colorado’s Report stated specifically that the state’s course and graduation requirements under § 22-1-104 are a condition of graduation.1

State Performance Plan / Annual Performance Report: Part B for STATE FORMULA GRANT PROGRAMS under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. For reporting on FFY18, Colorado included the state course requirement under § 22-1-104 CRS as a condition of graduation.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Colorado Department of Education Performance Plan PART B, P. 7 , www.cde.state.co.us/cdesped/spp-apr

· Provide a narrative that describes the conditions youth must meet in order to graduate with a regular high school diploma and, if different, the conditions that youth with IEPs must meet in order to graduate with a regular high school diploma. If there is a difference, explain.

· Under Colorado law, “each school district board of education retains the authority to develop its own unique high school graduation requirements, so long as those local high school graduation requirements meet or exceed any minimum standards or basic core competencies or skills identified in the comprehensive set of guidelines for high school graduation developed by the state board pursuant to this paragraph.” 22-2-106(1)(a.5) C.R.S. There are no specific courses, or numbers of courses, required by the state’s graduation guidelines, and there are no legislated course requirements other than one course in Civics: “Satisfactory completion of a course on the civil government of the United States and the state of Colorado . . . shall be a condition of high school graduation in the public schools of this state.” 22-1-104 (3)(a) C.R.S. Youth with IEPs must meet the same requirements as youth without IEPs in order to graduate with a regular high school diploma.

If Colorado is receiving any of this funding, it is obligated to address American Indian student needs, including the “lack of appropriate cultural awareness in school curriculum focusing on Native American history or culture” given the Findings of the Commission that this omission can (1) be harmful to American Indian students; (2) contribute to a negative learning environment; (3) trigger bullying; and (4) result in negative stereotypes across the board. Other minorities are similarly situated.

NOTES

1. IDEA CO DOE Performance Plan

https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdesped/spp-aprion (accessed online March 5, 2021).

PART 5: Colorado Education Associations

Colorado Education Association Supports C.R.S. § § 22-1-104 (1)-(6) (aka HB 19-1192)

CEA supports culturally relevant curriculum and supports the inclusion of local voices of community, parents, and educators in providing input and guidance in the decisions made in schools and districts.1

Colorado Association of School Boards (“CASB”) Legal Opinion on § 22-1-104

It may be that school districts are relying on the legal opinion of the CASB, dated May 2, 2018, in a letter sent to the CO DOE by Jenna Zerylnick, Legal Counsel for CASB:

State law contains a civics requirement, though it does not mandate an assessment method for civics competency. C.R.S. § 22-1-104(3)(a) provides: "Satisfactory completion of a course on the civil government of the United States and the state of Colorado. which includes the subjects described in subsection (2) of this section, shall be a condition of high school graduation in the public schools of this state."

… “Notably, the civics statute does not grant rulemaking authority to the State Board.

Further, it is not clear that the civics statute is constitutional, as it mandates that all public schools in the state teach certain topics and information. The issue has not been litigated. However, even if the civics statute were constitutional, under this statute, local school boards still retain control over instruction, curriculum and assessment methods.

Regardless of the constitutionality of the statute, the statute does not mandate an assessment method for civics competency nor does it grant rulemaking authority permitting the State Board to do so.”2

Ken DeLay, Executive Director, Colorado Association of School Boards

Michelle Murphy, Executive Director, Colorado Rural Schools Alliance

This is in direct contradiction of the 1983 CO Attorney General’s Opinion and the Skipworth case.

CASB’s Policy on Graduation Requirements - Recommended Language for CO School Districts that Best Meets Intent of Law, includes § 22-1-104(2) Civics Course

However, its current Policy on Graduation Requirements includes § 22-1-104.

“NOTE: State law requires all students to satisfactorily complete a course on the civil government of the State of Colorado and the United States (civics). C.R.S. 22-1-104. The Board has discretion to determine how the subject areas specified in C.R.S. 22-1-104, as well as the number of required credits, will be addressed when establishing graduation requirements for civics.” CASB’s C.R.S. 22-1-104 link in its CASB IKF Policy is to the 2020 version of the law.

NOTE: A local board may choose to require students to complete specific courses as part of its graduation requirements and identify them here. Please note that state law requires all students to satisfactorily complete a course on the civil government of the State of Colorado and the United States (civics). C.R.S. 22-1-104 3

CASB, Colorado Association of School Executives (“CASE”) and Colorado Education Association (“CEA”) Joint Influence over Legislature and CO DOE

Ken Delay, CASB’s executive director, said summit input will be very helpful in developing joint positions with the other associations on ESSA rules and regulations to take up with the State Board and in the General Assembly when legislators take up ESSA implementation in January. “If you haven’t been there, you can’t appreciate how much power there is in the Colorado Legislature when CASE, CEA and CASB all show up and say the same thing. It’s a big deal.”4

NOTES

1. http://scorecard.coloradoea.org/2019/bills/hb-19-1192/ (accessed online January 5, 2021).

2. Letter from the Colorado Association of School Boards (“CASB”) to the CO DOE, dated May 2, 2018, CDE Records

https://go.boarddocs.com/co/cde/Board.nsf/files/AYLJUG4CF82E/$file/Public%20letters%20on%20ss%20standards.pdf (accessed online January 5, 2021).

3. CASB IKF Policy

https://z2.ctspublish.com/casb/DocViewer.jsp?doccode=z20000254&z2collection=core (accessed online January 5, 2021).

4. https://ceawhatworks.wordpress.com/category/public-education/ June 2016 (accessed online March 1, 2021).

Part 6: Brief History of American Indian Education

Troubling Legacy

The topic of education is still troubling today to American Indians. Education was seen as a mechanism for the ‘absorption of tribes and extinguishment of reservations’ by assimilating Indians. This is signified by the famous 1892 quote: ‘kill the Indian in him, and save the man.’1 It was hoped that Indians would cease to exist as a distinct people, merging with the white communities engulfing them. Yet many Indians refused to give up their individual tribal identities and cultures. Their refusal was costly – they dropped out of the punitive education systems they encountered. Others, longing for acceptance, chose affirmation and approval, relinquishing their Indian identities.

American Indian tribes ceded over a billion acres of land and tribes were assured in return that the federal government would deliver educational services, medical care, and technical and agricultural training

Kennedy Report in 1969: Non-Indian Teachers and Children Misunderstand Indian Culture and History

In 1969, the Committee on Indian Education submitted a discouraging report entitled Indian Education: A National Tragedy-A National Challenge, also known as the Kennedy Report. The report claimed that one of the main problems with public school education for American Indian children was that non-Indian teachers and children misunderstood Indian culture and history. We have not advanced far beyond this.

National Congress of American Indians Report: Erasure from Education Fuels Harmful Biases

The National Congress of American Indians (“NCAI”), the largest and most representative national organization serving the interests of Indian Nations, commissioned a nation-wide study of public school education regarding Indians, including Colorado. The 2016-2018 Reclaiming Native Truth (RNT) project found that the invisibility of Native peoples is pervasive and entrenched across all sectors of American society.

It concluded as follows:

The invisibility of Native peoples and the erasure of contemporary Native Americans’ contributions, innovations, and accomplishments in K-12 education fuels harmful biases in generation after generation of Americans who grow up learning a false, distorted narrative about Native Americans. In most schools, information about Native peoples is either completely absent from the classroom or relegated to brief mentions, negative information, antiquated references, or inaccurate stereotypes. According to the RNT research, teaching students accurate Native history is not enough to break through the invisibility and stereotypes that feed and perpetuate bias and racism; it is also imperative to teach about contemporary Native issues and the accomplishments of Native peoples today.2

NCAI’s purpose for issuing the Report was for it to “serve as a platform to build momentum, engagement and support for a movement to transform K-12 education to accurately represent Native peoples’ cultures, histories, diversity, contributions, and contemporary place in today’s society.”

Contemporary Stereotypes Regarding Indians: Rick Santorum

In April 2021, former U.S. Senator Rick Santorum stated that there was "nothing here" before European settlers arrived. His comment exposes the grave need for Indian curriculum.

"We came here and created a blank slate," Santorum said. "We birthed a nation from nothing. I mean, there was nothing here. I mean, yes we have Native Americans, but candidly there isn't much Native American culture in American culture."3

Fawn Sharp, president of the NCAI, countered his statement with the fact that European colonizers found "thousands of complex, sophisticated, and sovereign Tribal Nations, each with millennia of distinct cultural, spiritual and technological development."4

He ended up losing his position as a CNN commentator.

NOTES

1. Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction (1892), 46–59. Reprinted in Richard H. Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites,” Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973), 260–71;

https://upstanderproject.org/firstlight/pratt (accessed online January 5, 2021).

2. Reclaiming Native Truth (2018). Research Findings: Compilation of All Research. Echo Hawk Consulting & First Nations Development Institute, June 2018.

3. https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/tv/2021/04/26/rick-santorum-dismisses-native-american-culture-spurring-backlash/7384340002/ (accessed online April 30, 2021).

4. https://www.ncai.org/news/articles/2021/04/26/ncai-president-fawn-sharp-s-statement-re-rick-santorum-comments-to-young-american-foundation (accessed online April 30, 2021).

PART 7: Colorado Academic Standards: History and Development

Standards for student learning are not new in Colorado. Passed in 1993, House Bill 93-1313 initiated standards based education Colorado. The statute required the state to create standards in reading, writing, mathematics, science, history, civics, geography, economics, art, music and physical education.

1998 Colorado Model Content Standards for Civics

Even though 22-1-104 required teaching about the history, culture and social contributions of Spanish-Americans and American Negroes, there are only two references to American Negro issues. American Indians were added April 17, 1998 so they were not addressed in these Standards, though the statute adding American Indians did not require standards to start teaching about the history, culture and social contributions of American Indian.

Civics, Grades 9-12 As students in grades 9-12 extend their knowledge, what they know and are able to do includes

· developing, evaluating, and defending positions about historical and contemporary efforts to act according to constitutional principles (for example, abolition movement, desegregation of schools, civil rights movements) and …

· analyzing, using historical and contemporary examples, the meaning and significance of the idea of equal protection* of laws for all persons (for example, Brown v. Board of Education, University of California v. Bakke)…. 1

2009 Civics Standards for High School

No reference to 22-1-104 or African Americans, American Indians or Hispanics or other terms for these groups, i.e., Native Americans.2 This is confirmed by Connor Kirwan Warner, in his study of state social studies standards for American Indian education, which included Colorado.

He found that Colorado does not specify any concrete information that students must learn about living American Indians (Colorado Department of Education, 2009). 3

2013 Colorado's District Sample Curriculum Project

The 2013 teacher-authored High School, Social Studies Complete Sample Curriculum created during Colorado's District Sample Curriculum Project in 2013 has NO references to Indians or tribes, Blacks (Africans, Negroes), Hispanics or Latinos or Spanish-Americans. The authors of the Sample were Rachel Nelson (Plateau Valley 50) and Janis Schimmel (Cherry Creek).4

2020 Civics Standards for High School: Address Indian History, Culture and Social Contributions by Merely Inserting Word “Tribal” Wherever List of Governmental Entities Occurred

In 2020, the CO DOE promulgated Social Studies Standards and noted that school district compliance with § 22-1-104 is required. These Standards remain in full force and effect until superseded. They addressed Indian history, culture and social contributions by merely inserting the word “tribal” wherever a list of governmental entities occurred:

Participate in civil society at any of the levels of government, local, state, tribal, national, or international.

Participation in a local, state, tribal, or national issue involves research, planning, and implementing appropriate civic engagement

Civic-minded individuals understand how the U.S. system of government functions at the local, state, tribal, and federal level in respect to separation of powers and checks and balances and their impact on policy.

Assess how members of a civil society can impact public policy on local, state, tribal, national, or international issues. For example: voting, participation in primaries and general elections, and contact with elected officials.

Nature and Skills of Civics:

1. Civic-minded individuals use appropriate deliberative processes in multiple settings, such as caucuses, civic organizations, or advocating for change at the local, state, tribal, national or international levels.

3. Civic-minded individuals evaluate citizens’ and institutions’ effectiveness in addressing social and political problems at the local, state, tribal, national, and/or international levels.

5. Civic-minded individuals analyze how people can use civic organizations, and social networks, including media to challenge local, state, tribal, national, and international laws that address a variety of public issues.

7. Civic-minded individuals evaluate multiple procedures for making and influencing governmental decisions at the local, state, tribal, national, and international levels in terms of the civic purposes achieved.5

State of State Standards for Civics and U.S. History in 2021; Colorado Receives Grade of ‘D’

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a renowned research, analysis, and commentator on education, conducted a review of the states’ standards for Civics and U.S. History.6 For Colorado, it reviewed: “Colorado Academic Standards: Social Studies,” 2020, https://www.cde.state.co.us/ cosocialstudies/2020cas-ss-p12.

Overview:

Its June 2021 analysis concluded that Colorado’s civics and U.S. History standards are inadequate. In general, they fail to specifically reference essential content, and the sporadic lists of persons or events that accompany the broad grade-level expectations don’t delineate a proper scope or sequence. A complete revision of the standards is recommended.

Civics: D

Content & Rigor: 2/7

Clarity & Organization: 1/3

Total Score: 3/10

U.S. History: D

Content & Rigor: 2/7

Clarity & Organization: 1/3

Total Score: 3/10

Civics

Strengths 1. The content for early grades is generally age appropriate and often quite specific. Weaknesses

1. Many standards are too broad and vague to provide useful guidance.

2. Most essential content is missing at the high school level.

3. Organization is needlessly complex and confusing.

History

Strengths 1. There is considerable emphasis on history-related analytical and research skills.

Weaknesses

1. Historical content guidance is extremely thin, thematically scattered, and stripped of context.

2. The Colonial era is relegated to grade 5.

3. The complex organizational structure is needlessly confusing and often redundant.

Dr. Amber Northern, Senior Vice President for Research with The Thomas B. Fordham Institute interview with Ross Kaminsky on June 24, 2021, described Colorado’s standards as “wishy-washy”, “vague and amorphous.” “The lack of detail is problematic.” It’s a “recipe for disaster” in holding students accountable. It’s a “travesty” for the children of Colorado. Politically they aren’t likely to offend anyone because they don’t say anything. Colorado needs to “go back to the drawing board.”7

2021 SB 21-067 Civics Standards to Be Developed as Soon as Is Practicable

The Colorado state legislature requires standards to be developed under the legislation for civics added by SB 21-067: As soon as is practicable after the effective date of this subsection, the state board of education shall review the civics portion of the social studies standards and revise them as necessary to comply with the requirements of subsection (1)(b) of this section. The state board of education shall take into consideration any recommendations of the history, culture, social contributions, and civil government in education commission established in section 22-1-104.3 in reviewing the civics standards pursuant to this subsection (1)(c). (Emphasis added.)8

(c) NOTWITHSTANDING THE REQUIREMENT IN SECTION 22-7-1005 (6) PAGE 4-SENATE BILL 21-067 TO REVIEW THE PRESCHOOL THROUGH ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION STANDARDS EVERY SIX YEARS, AS SOON AS IS PRACTICABLE AFTER THE EFFECTIVE DATE OF THIS SUBSECTION (1)(c), THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION SHALL REVIEW THE CIVICS PORTION OF THE SOCIAL STUDIES STANDARDS AND REVISE THEM AS NECESSARY TO COMPLY WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF SUBSECTION (1)(b) OF THIS SECTION. THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION SHALL TAKE INTO CONSIDERATION ANY RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE HISTORY, CULTURE, SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS, AND CIVIL GOVERNMENT IN EDUCATION COMMISSION ESTABLISHED IN SECTION 22-1-104.3 IN REVIEWING THE CIVICS STANDARDS PURSUANT TO THIS SUBSECTION (1)(c).

CCSD’s Social Studies Curricular Resource Review Implementation Scheduled for 2024-2025

On April 23, 2021, the CCSD’s Social Studies Curricular Resource Review was presented to the CCSD BOE reflecting a timeline of possible implementation of Social Studies curriculum revisions in 2024-2025. There is no mention whatsoever of § 22-1-104. The schedule presented to the CCSD BOE states:

Transition: Plan and Design will be developed in 2022-2023.

Transition: Test and Refine will be done in 2023-2024.

Implementation is not scheduled until 2024-2025.

Implementation and Refine is scheduled for 2025-2026

Subsequent Revision 2026-2027. (Emphasis added.)9

Sarah Grobbel, CCSD’s Assistant Superintendent for Career, Innovation, and Student Engagement reported that the HB 19-1192 Commission began meeting in 2019 and gave its completed recommendations to CDE just last month. “Next,” she said, “CDE will spend this whole next year…looking at what the new revised standards should be based on those recommendations, while the commission spends the next two years curating different curricular resources that they can share across Colorado to our school districts.” Then CCSD “will have two years after we get the new revised standards to transition, plan, design, then test and refine the instruction that we are going to put in front of our kids before we fully implement (the revised standards)” in the 2024-2025 school year, according to the illustrative timeline presented at the meeting.10

CCSD’s plan is not in accord with the statute.

Number 1: As of 2007, they should have already been teaching a civil government course with Indian history, culture and social contributions, and no student should have been allowed to graduate without successfully completing this course. ….

2. No statute permits “CDE this whole next year…looking at what the new revised standards should be based on those recommendations, while the commission spends the next two years curating different curricular resources that they can share across Colorado to our school districts.”11

3. No statute permits the Commission another two years to curate resources.

4. No statute permits CCSD another two years after that to implement 22-2-104(1).

Culturally Responsive Instruction for Native American Students

Title VI, Part A of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act is designed to ensure that American Indian, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native students meet challenging state academic content and student academic achievement standards, as well as meet their unique culturally related needs.

In 2018, the CDE made the following series available on its Title VI site:

Culturally Responsive Instruction for Native American Students

It currently addresses the following questions.

· What is culturally responsive instruction?

· Why is it important for Native American students?

· How does culturally responsive instruction connect to traditional Native American educational approaches?

· What are specific guidelines for providing culturally responsive instruction for Native students?

· What does culturally responsive practice look like in different subject areas?

· What are the steps to take to develop a culturally responsive practice?12

Colorado’s Black, Latin and LGBTQ Legislative Caucuses and Education Committee Concerned about Educational Achievement Gaps for Minority Students in Colorado

Colorado’s Black, Latin and LGBTQ Legislative Caucuses and Education Committee are all concerned about educational achievement gaps for minority students occurring in Colorado. To investigate this matter, Senators Rodriguez, Buckner, Gonzales, Moreno, Pettersen, Story, Zenzinger and Garcia, along with Representatives Gutierrez, Duran, Amabile, Bacon, Benavidez, Bernett, Caraveo, Cutter, Froelich, Hooton, Jackson, Kennedy, Kipp, McCormick, Ortiz, Sirota, Snyder, Weissman, Woodrow, Young, Boesenecker, Esgar, Exum, Gray, Herod, McLachlan, Michaelson-Jenet, Ricks, Titone, Jodeh and McCluskie introduced legislation for an audit.

A major sponsor of the legislation (HB 21-1294), Senator Robert Rodriguez of Denver, wanted an audit to consider whether aspects of Colorado’s’ education accountability system “maintain institutional or cultural biases.” To get the Bill passed, he had to agree to a change in the language to whether “unintended barriers or obstacles” affect the performance of students from different groups. It was signed by Governor Polis on July 2, 2021.13

Statement of Problem in Pathways to Sovereignty

In “Pathways to Education Sovereignty: Taking a Stand for Native Children Presented by the Tribal Education Alliance, New Mexico,” the problem with the biased education in public schools is clearly stated: the schools are absolutely and completely ‘resistant to change’ and the ‘historical injustices’ of failures to comply with the law continue unabated, without consequences, except to Indian children who are irreparably harmed.

Native children have the right to an adequate and sufficient education, but at each stage of their lives the public education system fails them. From early childhood through primary, secondary and post-secondary schooling, the cumulative effect of under-resourced, misguided and — to this day — biased educational inputs produces disparate educational outcomes. This systemic equity gap in education jeopardizes the future of Native students and the future of tribal communities.14

Over two years later, the state has yet to make meaningful investments in Native children. It has yet to embrace a shift in attitude and approach. Instead, a pattern of resistance to change emerged. 15

The continuum of historical injustices, present day failures to comply with laws and court orders, and the prospect of losing future generations to a Western way of life is evident to New Mexico’s Nations, Tribes and Pueblos. 16

NOTES

1. https://web.archive.org/web/20120604213522/ http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdeassess/documents/OSA/standards/civics.pdf (accessed online August 15, 2021).

2. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cosocialstudies/cas-socialstudies-p12-pdf (accessed online August 15, 2021).

3. Warner, C.K. (2015). A study of state social studies standards for American Indian education. Multicultural Perspectives, 17(3), 9. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281059261_A_Study_of_State_Social_Studies_Standards_for_American_Indian_Education (accessed online September 5, 2021).

4. https://www.cde.state.co.us/standardsandinstruction/curriculumoverviews-bygrade#HS (accessed online August 15, 2021).

5. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cosocialstudies/statestandards (accessed online August 15, 2021).

6. https://fordhaminstitute.org/sites/default/files/publication/pdfs/20210623-state-state-standards-civics-and-us-history-20210.pdf (accessed online September 5, 2021).

https://www.coloradopolitics.com/opinion/the-podium-colorado-schools-flunk-history/article_ebf7c332-fa6b-11eb-9424-07833425e760.html (accessed online September 5, 2021).

7. https://www.facebook.com/630KHOW/videos/amber-northern-joins-ross/1217136642066940/ June 24, 2021 (accessed online September 5, 2021).

8. https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/2021a_067_signed.pdf (accessed online August 15, 2021).

9. Regular Board of Education Meeting, June 23, 2021, Board of Education, Cherry Creek School District

https://go.boarddocs.com/co/chcr/Board.nsf/Public (accessed online August 15, 2021).

10. Creek Schools: We Don’t Teach Critical Race Theory, The Villager, June 30, 2021, Freda Miklin

https://villagerpublishing.com/cherry-creek-schools-we-dont-teach-critical-race-theory/ (accessed online August 15, 2021).

11. Ibid.

12. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cde_english/titlevi (accessed online August 29, 2021).

13. https://co.chalkbeat.org/2021/6/4/22519284/colorado-school-ratings-accountability-system-audit-bias (accessed online August 29, 2021).

14. Pathways to Education Sovereignty: Taking a Stand for Native Children Presented by the Tribal Education Alliance, New Mexico, p. 7.

https://nabpi.unm.edu/assets/documents/tea-full-report_12-14-20.pdf (accessed online September 5, 2021).

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., p. 14.

PART 8: Holocaust and Genocide Education in Colorado Public Schools

Within less than one year, the CO DOE adopted standards for Holocaust and Genocide Education in Colorado Public Schools. On July 8, 2020, Governor Polis signed into law HB20 – 1336. This legislation includes several elements focusing on the teaching of the Holocaust and Genocide in Colorado. Specifically, on or before July 1, 2023, each school district Board of Education and charter school shall incorporate academic standards on Holocaust and Genocide studies into an existing course that is currently a condition of high school graduation. Said standards shall be recommended by a stakeholder committee and adopted, on or before July 1, 2021, by the State Board of Education and should identify the knowledge and skills that students should acquire related to Holocaust and Genocide studies, including but not limited to the Armenian genocide. In addition, the CDE shall create and maintain a publicly available resource bank of materials pertaining to Holocaust and genocide, no later than July 1, 2021.1

NOTES

1. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cosocialstudies (accessed online August 15, 2021).

PART 9: Community Concerns with Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Indigenous Community Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum

Starting in October 2020, the Indigenous Parent Action Committee (“IPAC”) within the CCSD publicly addressed the need for the CCSD to comply with § 22-1-104. They had been petitioning the CCSD for the past decade for a curriculum addressing American Indians, with no success. IPAC is comprised of indigenous parents/guardians and staff. IPAC meets monthly and as delineated by the CCSD focuses on the following:

Illuminating the presence of CCSD's Indigenous community

Amplifying the voices of the Indigenous community by working directly with district leaders to make changes necessary to better serve Indigenous students and families

Forming cross-district partnerships to strengthen the Indigenous community network

Naming the continuous problems of practice embedded in the CCSD learning experience interfering with Indigenous students' academic and social-emotional success (i.e. problematic curriculum resources, erroneous representation and/or lack thereof, microaggressions, normalized harmful traditions/practices i.e. Halloween, Thanksgiving)

Affirming and honoring Indigenous students' presence and cultural identities1

This issue is pertinent in three other states: Montana, New Mexico and South Dakota:

1. Lawsuit Filed Against Montana Violating Constitutional Mandate to Teach Indian Education

2. Tribal Leaders Demand Action on Public Education Inequity in New Mexico (Including Implementing Culturally Relevant Curriculum)

3. South Dakota: Native History Gutted In School Curriculum

https://www.indianz.com/News/2021/08/16/harold-frazier-native-history-gutted-in-school-curriculum/

CCSD’s Students’ Concerned with CCSD’s Non-Inclusive Curriculum2

In a March 9, 2021, article in the Grandview High School Chronicle, a discussion on curriculum revealed the effort needed for a more inclusive curriculum. I have redacted the names of individuals.

One group can only stay silent for so long in oppression before they rise up against their oppressors. An event we have seen play out thousands of times throughout history. One of which is now occurring within Grandview.

“There are just a ton of issues in all departments,” said senior, Kayla

Espinosa.